There’s a moment in Steve Jobs, one of those dangerous little intervals between a volley of Sorkinian wit and the next bracing clash of egos when you realize: this is not, and never has been, about computers. It’s about the performance, jobs (no pun intended) as theater, invention as drama, genius as soliloquy. The curtain rises, the orchestra tunes, and our hero snappish, mercurial, blazingly single-minded, takes center stage, a maestro of microchips who can’t solder a wire but can bend the collective will of a room as if it were his own personal instrument. Aaron Sorkin has never met a conference room he couldn’t set aflame with words, but Danny Boyle, all kinetic energy and pulsing light, turns these corridors and backstage wings into a kind of nervy, flickering proscenium. Forget the dreary rest of the “biopic” genre; Steve Jobs isn’t here to teach you the story of Apple. It’s here to make you feel that strange, unholy exhilaration of watching the right mind crash mercilessly, ecstatically, against the world.

This isn’t the cradle-to-grave trudge of your average Oscar-hungry biographies, and mercifully, it is nothing like that other Jobs picture, the Kit-Kat bar in the vending machine of celebrity hagiographies that was the Ashton Kutcher “Jobs.” Sorkin, in his element, slices fourteen years of myth into three acts, each a prelude to performance, Macintosh, NeXT, and iMac, reheating the eternal backstage drama with the urgency of opening night. The freedom from chronological soup is a liberation. We aren’t asked to believe a man can be “explained” by a succession of haircuts and t-shirts, but swept up in the mounting, unspooling immediacy of great theater: a man at war with his colleagues, his own monstrous ambition, and the inconvenient, insistent presence of his neglected, unforgiving daughter.

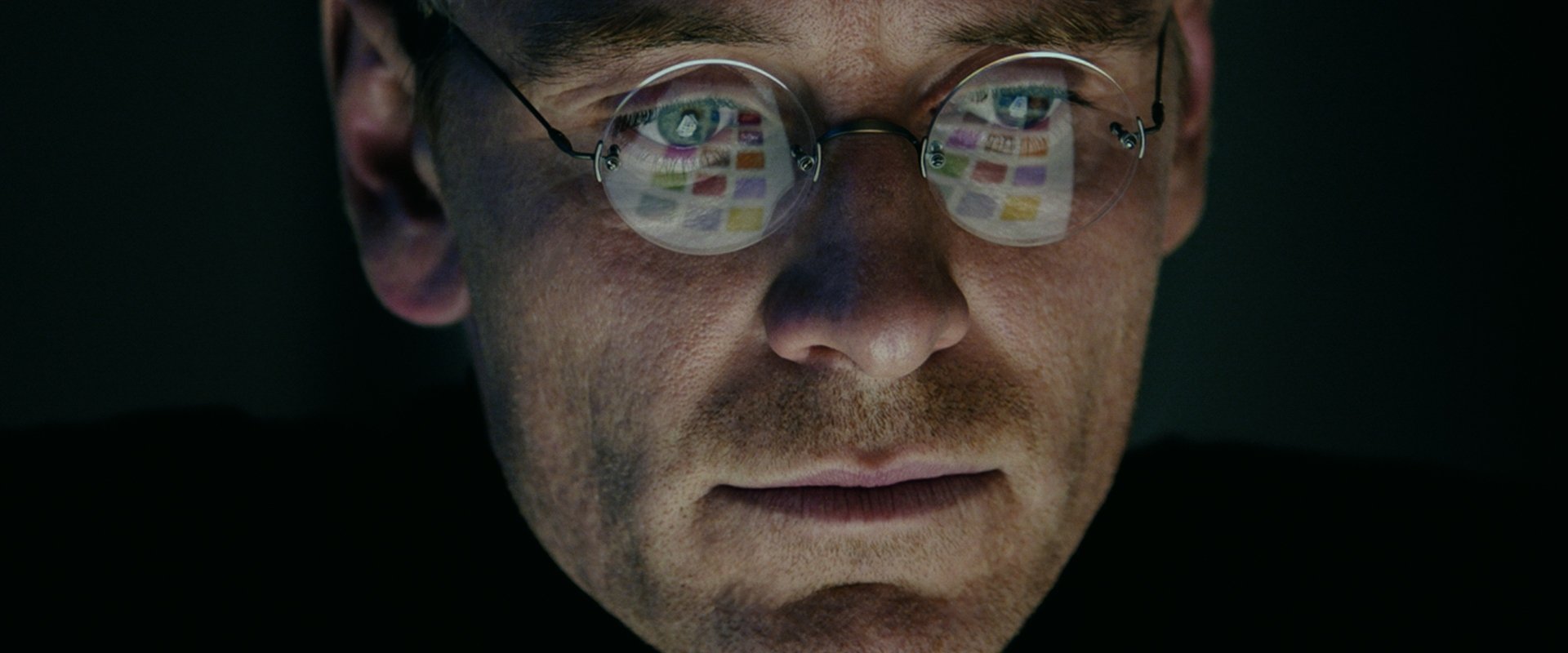

To call this film dialogue-driven is like saying Beethoven composed a few nice tunes, Sorkin’s script crackles. The arguments aren’t mere squabbles; they’re conducted at the white heat of necessity, the rhythm of a world that demands a Steve Jobs, and just as quickly spits him out when the friction gets too much for polite company. What a joy to watch Michael Fassbender, the canonically un-Jobs-looking Jobs inhabit this creation. He’s not performing a Xerox of the turtleneck, a museum-quality waxwork impression but something at once sharper, sadder, and more magnetic: a man haunted by his own vision and by the impossibility of satisfying it, either in silicon or in flesh and blood. His Steve doesn’t beg us to love him, a relief. Somehow, by the last act, we do anyway.

There’s an athletic pleasure in watching him spar with Seth Rogen’s Steve Wozniak like Charlie Parker trying to explain jazz to a great technician. Their arguments aren’t just about credit or childhood pain. They’re about the agony of being necessary to each other: the poet and the mathematician, each lost without his opposite number, doomed to dance the same fight forever. When Wozniak hurls his now-famous, acid lines, “What do you do?”, it’s both a primal scream and a love letter. Rogen, loose and defensive, is a revelation he’s playing the straight man who can never quite escape the joke at his own expense.

Then, pirouetting through the carnage, is Kate Winslet’s Joanna Hoffman. Intelligent, weary, and astonishingly credible beneath a Slavic accent that would’ve felled a lesser actor, Winslet is the best “work wife” a titan of industry ever had, his conscience, his sparring partner, his only reliable tether to messy, recalcitrant humanity. It’s a plum of a role, but Winslet nourishes it with a mix of discipline and bruised affection, never merely the caretaker or the scold. Their scenes, her voice slicing through Fassbender’s iron, are the movie’s heartbeat, less a corrective than a reminder of what’s at stake when you turn your whole existence into a quest for “perfection.”

What is innovation, the movie keeps asking, if it costs you every scrap of decency on the way? Sorkin, no innocent about monstrous ambition, lays out the case and then lets us taste the blood. Jeff Daniels, ripe with boardroom gravitas and fatherly disappointment as John Sculley, gives his own exiled king performance, alternately remorseful and righteous as Jobs’ Apple world collapses and reshuffles. The Sculley-Jobs collision, played twice, like a melody in minor and major anchors the film’s sense of tragedy. These are men incapable of loving each other, united only by their understanding that greatness, in America, is something that comes at the cost of everything else.

Boyle, for his part, directs less with reverence than with speed. Where Fincher (that watchmaker of “The Social Network”) would have carved this material into icy precision, Boyle sets it racing: you can practically taste the sweat of the green room, hear the near-manic hum of anticipation behind every tempestuous exchange. Through it all, the film isn’t afraid to be messy, to let brilliance and petulance spill over into the aisles. All biographical movies claim to “capture the essence”, but this one does not merely capture, it distills, reducing a life to its rawest, most vital arguments, and trusting us to feel the symphony in its discord.

If there are complaints, they belong to the historians, yes, events are compressed, emotional truths dipped in the candy shell of fiction. But “Steve Jobs” isn’t interested in embalming fact. It’s a high-wire performance, a film about the performance of genius, the spectacle of leadership, the carnival of not quite being human in pursuit of an idea. It leaves you a bit breathless, giddy, even for remembering, if only for a moment, what creativity looks like before the culture squeezes it flat. What do you do, Steve? You play the orchestra. And Boyle, crashing cymbals and all, plays a hell of one himself.