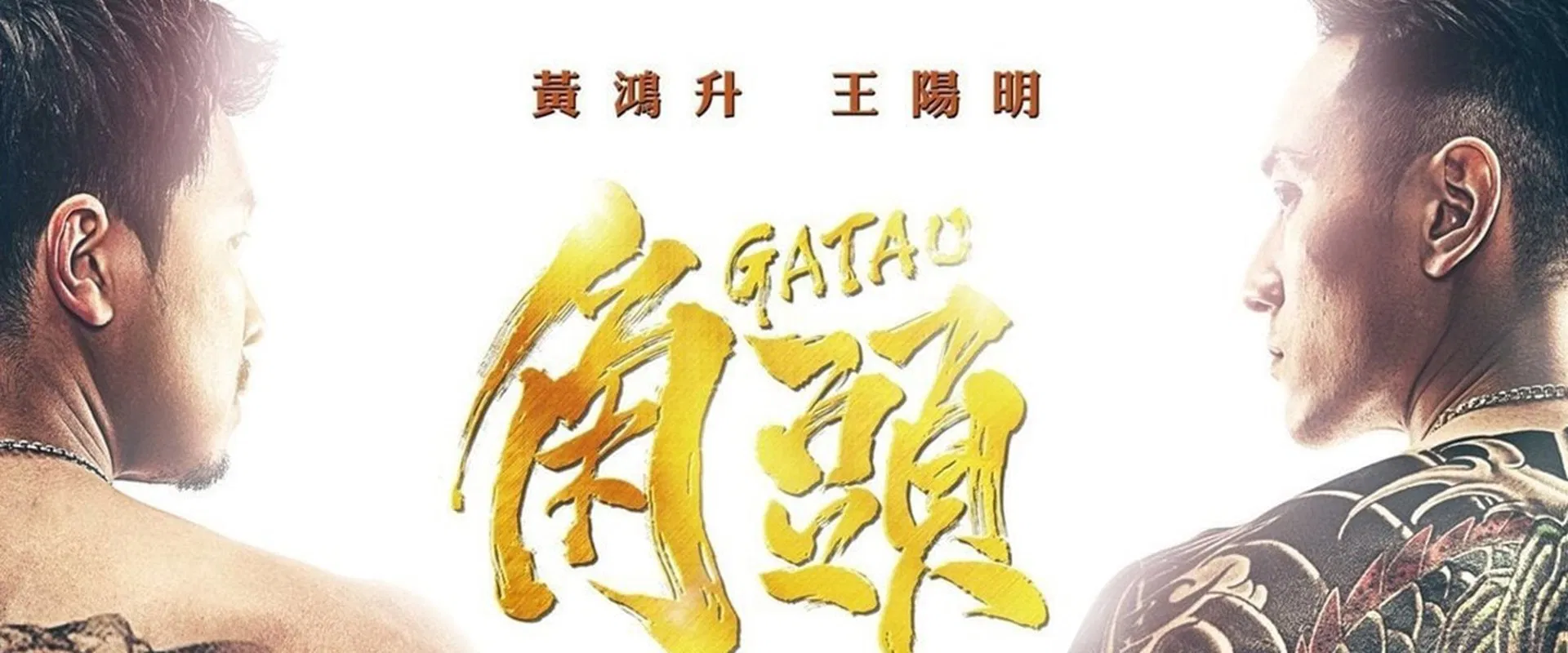

What does it mean for a gangster film—not just in Taiwan, but anywhere in the world—to recite all the liturgies of brotherhood, blood, and betrayal, but leave you with nothing more than the memory of flickering shadows on a wall? Joe Lee’s Gatao (2015) is exactly that: a movie that earnestly checks the boxes of triad cinema, hoping to conjure up some of the lurid energy that made Hong Kong’s Young and Dangerous a pop touchstone—but ending up more like a karaoke version sung after midnight, charming in its recognizability, but never threatening to set the night on fire.

Watching Gatao, I kept waiting for something—anything—to ignite. This is a film so determined to honor its genre forebears that every beat feels airlifted from a textbook: the honorable lieutenant with the furrowed brow (Huang Hongsheng, giving the sort of solid but stifled performance usually reserved for supporting roles), the loyal friend (Sun Peng), the U.S.-educated upstart returning to reclaim his family’s turf. It’s a generational chessboard whose every move is so familiar, I sometimes felt the movie was acting out an elaborate ritual whose outcome had been ordained decades before.

Joe Lee seems to want to imbue his film with a gritty, streetside authenticity—a yearning that’s persistently thwarted by creaky resources and uninspired writing. The fights are staged with a self-consciousness that leaves you wincing for all the wrong reasons: deadly serious faces contorting with the effort of not slipping on fake blood or bumping into a clearly rubber knife. There’s a kind of community-theater earnestness here—fight scenes that aspire to Johnnie To but rarely rise past high school pep rally.

Which brings us to the dialogue—a parade of familiar pronouncements about brotherhood, duty, and the inevitable cost of betrayal. The words clatter to the ground, never offering the actors a rung to climb closer toward actual human feeling. The script, convinced that exposition equals depth, serves up the hearts and dreams of its characters with the whiff of plot summary. Even the women, already ornamental as per genre standards, are here given precious little to do except look worried or sing the same dangerous duet of romantic peril.

If Gatao had any pretensions of upending the crime genre, they’ve been well hidden. It’s not that the director is unaware of great triad cinema—rather, he’s too reverent. Monga, made just a few years prior, found a way to enliven these worn themes with heat and style. Hong Kong’s Young and Dangerous movies, for all their melodrama, radiated a trashy charisma that made every back-alley brawl feel like grand opera compared to Gatao’s polite community skirmishes.

One might excuse some of these failings on the altar of budget—after all, who can compete with the firepower of the golden age of Hong Kong cinema? But even at a cut-rate production level, a filmmaker with daring or perverse invention can unsettle, amuse, or surprise. Here, the mood is reliably grim but never electric, and the themes—loyalty, ambition, the melancholy price of power—are recited like a catechism, stripped of the fever that could sting or soothe.

There’s one gunfight, a would-be climax, that instead detonates the illusion of drama entirely—it’s so absurdly choreographed that you almost hope Lee is reaching for Samuel Fuller kitsch. But no: this is a film allergic to pulp excess, settled instead on a steady hum of mediocrity.

To say Gatao is “good” is to admit a certain soft spot for competence and genre comfort. It’s not a disaster, and its familiarity has a vague, comforting rhythm. But like an old photo album, it’s strictly for those content to leaf through memories of better, wilder nights. If you’re seeking new wonders in the underworld, you’re better off with Monga or a return visit to Chan Ho Sun’s Hong Kong street gangs, where every cliché at least comes with a spark.

Here, those sparks never quite catch. Gatao doesn’t remake the gangster film into a savage allegory of divided loyalties or a bittersweet hymn to lost brotherhood. It simply marks time, delivering an echo of triad cinema without the pulse. As a genre exercise, it’s passable in the way a supermarket croissant reminds one, dimly, of Paris: you recognize the shape, but the taste fades instantly.