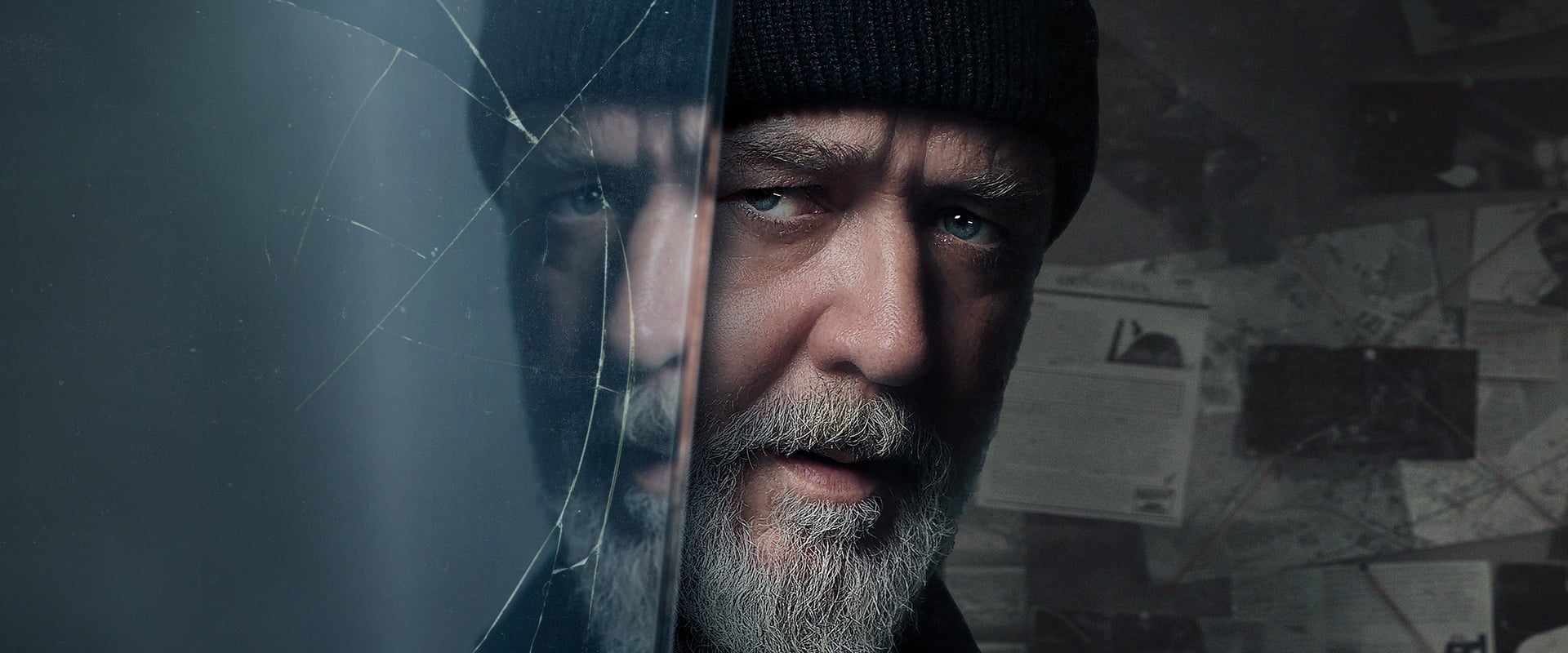

There’s something almost illicit in the surprise of “Sleeping Dogs”—as if you’d gone to the usual midnight mass of generic thrillers and, in the half-light, found the sermon delivered by Russell Crowe, voice ragged, eyes veiled with embers of regret. In his hands, or more aptly in the shuffling gait and battered dignity of Roy Freeman, Adam Cooper’s directorial debut morphs, unexpectedly, into a meditation on the porousness of memory and the sleight-of-hand of self-forgiveness. If the movie pulls you forward with the sticky taffy of psychological suspense, it’s Crowe who gives the confection its bite.

From the outset, “Sleeping Dogs” doles out all the palate teasers of the genre—a retired detective, a cold case, a last shot at some kind of redemption, even if the only witness who remembers is swiftly being evicted from his own mind. Based on E.O. Chirovici’s “The Book of Mirrors” (that title alone promising the house-of-cards intricacies and existential vertigo Cooper mostly delivers), the script is a knotted string of betrayals and “ah-ha!” reversals: a slow burn that demands you settle in, quiet your pulse, and trust that what at first appears predictable will find its curves through character rather than calamity.

It’s the patience of the thing—the conviction that mystery can be its own reward, not merely a jump-scare machine—that feels so much more than a debutant’s lucky strike. Cooper (with co-writer Bill Collage) doesn’t rush toward narrative catharsis; he lets the rot seep through the paint, and the viewer with enough staying power is paid back, if not in the gold bullion of surprise, then in the silver half-dollars of emotional candor.

Let’s talk Crowe—how can we not? Crowe, bearing the weathered tenderness and the hunched, dogged physicality of a man half-drowned in his own past, moves through the film with the measured grief of a boxer who can’t remember what he’s fighting for, only that he must keep swinging. It’s the performance of an actor who knows how to make vulnerability pulse behind the knuckles—the anguish of a mind in retreat rendered as quietly as a trembling jaw or a gaze losing its anchor. Crowe’s Roy isn’t simply unraveling; he’s burning, gently, from the inside out. These are the textures of a performer who’s traveled from gladiator cliffs to these airless, internal sands—and is somehow all the more alive for it.

Around him circles a supporting cast, each orbiting with varied gravitational pull. Karen Gillan’s Laura Baines (and her doppelganger, Dr. Westlake) brings layers, yes, though her spare, at times staccato delivery sometimes leaves you craving a little more dissonance in her duets with Crowe. Yet what matters is the deepening of her character over time—a gradual reveal rather than a knock at the door. Tommy Flanagan as Roy’s ex-partner, all battered charm and shadowy self-interest, chews through his scenes in the way only Flanagan can: the movie lets its men be half-fallen idols and their women the misunderstood keepers of the flame, but at least no one here exists solely as a plot device. At best, they’re all walking secrets.

Cooper, miraculously for a filmmaker finding his sea legs, knows just when to hold a shot, how to let dread accrue in the angles of a claustrophobic room or a memory flickering at the edge of speech. There’s stylishness here but little bravado—this isn’t filmmaking that flaunts its own cleverness. The intelligence of the movie is in its refusal to go for cheap action or errant gunfire. Instead, it’s a collage of mood and minor-key sorrow, the camera lingering as if the lens itself were worried it might be forgetting.

If we’re to fault the adaptation (the script is too faithful, perhaps, to the book’s plotting maneuvers), it’s for the occasional lapses into dialogue a hair too arch or on-the-nose, moments that land with a thud rather than a thrum. But these are rare misfires in a tapestry otherwise woven with tact. The heart of the thing, after all, is in moments—shared strains between Roy and his estranged daughter, Susan (Paula Arundell), where the film lifts off the procedural grid and lets in some breathtaking humanity. These small, unhurried collisions ground the movie, letting Cooper’s careful pacing give way to something close to grace.

What lingers most is the atmosphere—a sustained shiver of unease, the sense that every shadow is a relic and every room a reliquary. The palette is nearly funereal; it matches Crowe’s slow disintegration, making the labyrinth of Roy’s mind indistinguishable from the cold, rain-smeared city beyond his window. The twists arrive, yes, and you see some coming, much as you sometimes hear the train before it emerges from the tunnel. But this is a thriller less about who did it than about who can survive knowing—who carries the memory, and who gets the reprieve of forgetfulness.

Does “Sleeping Dogs” reinvigorate the genre? No, but it has the honesty not to pretend it does. Instead, it carves out a moody, contemplative nook of its own—a room of regret and reluctant hope. Cooper’s debut encourages patience, thought, and, wonder of wonders, a little feeling. It’s the kind of film where the solution matters less than the protagonist’s weary struggle to remember anything at all, let alone the answer.

And Crowe? He carries the movie like a dowser wandering a psychic wasteland, his gifts undiminished, perhaps even sharpened by the soft-focus wounds. There are not many who can turn the gradual ebbing of self into something electric. Crowe here achieves that alchemy—reminding us that the real thrill, after all, isn’t the chase, but what it costs to run.

So give me this over a thousand flashy pretenders: “Sleeping Dogs” is the kind of small, fumbling triumph that makes you glad you showed up for the late show and let yourself remember what the movies—at their best—can make you feel.