Is there anything more perverse—and perversely funny—than watching Hugh Grant, that perennial celluloid charmer, take a swan dive into villainy? In “Heretic,” he does not merely play against type; he dances into the abyss with silk gloves on, turning neighborly warmth into menace so delicious it’s almost camp, except nothing about his performance feels accidental. You watch Grant, and it’s like seeing Cary Grant slip a knife between the ribs—a delight so vertiginous you can’t help but smile before the shiver hits.

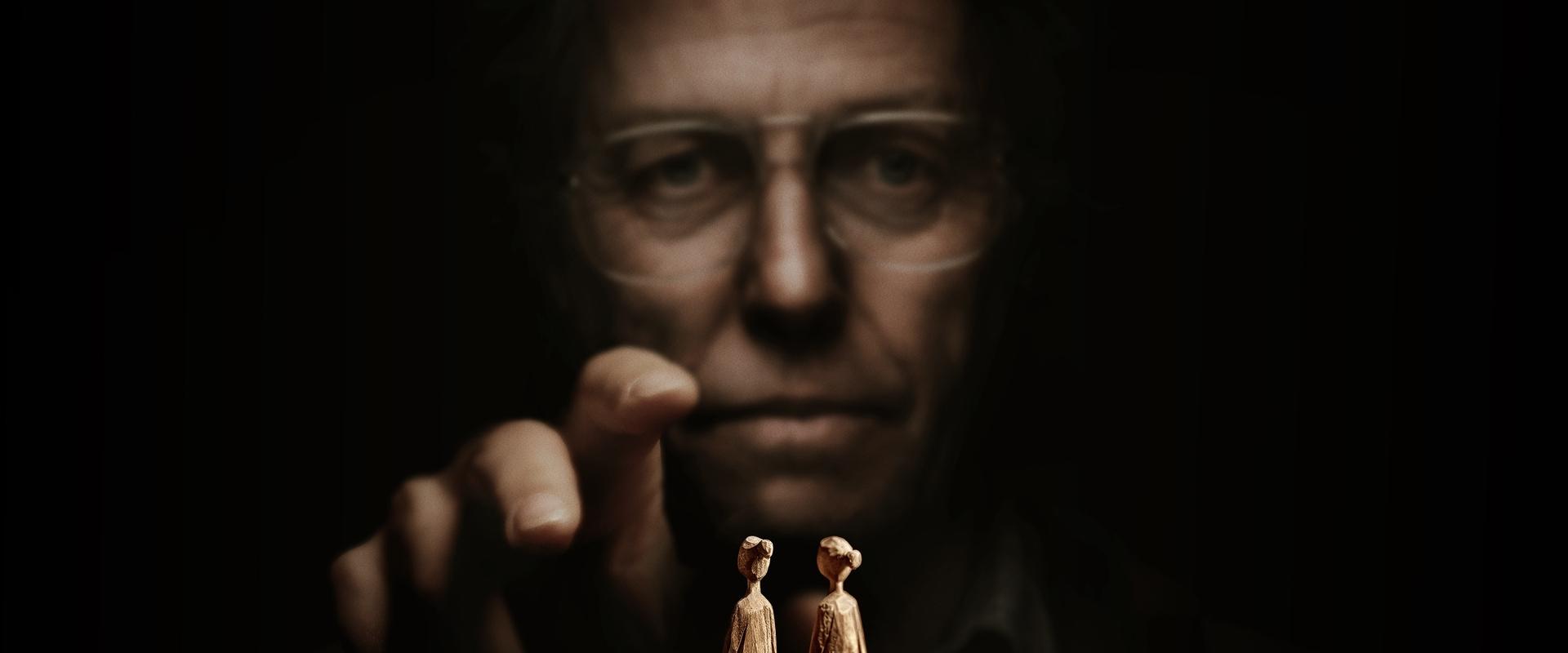

But “Heretic” is no mere star vehicle. It’s a film that drags you, willingly and then by force, into the marshy backroads of belief—where faith and control tango with psychology, and every answer tastes just a bit off, like communion wine gone sour. The movie’s setup is the suspense of simplicity: two missionaries, fresher than daisies—Sophie Thatcher’s Sister Barnes, who radiates grit, and Chloe East’s heartbreakingly tremulous Sister Paxton—knock on Grant’s Mr. Reed’s door, and before you can say “the devil’s in the details,” they realize they’re not getting out. The house becomes a pitiless confessional, all drafts and shutting doors, and the pious banter takes on the ring of interrogation.

And yet, what a glorious, frightening ride it is—at least until that final act, where the film seems to lose its own faith. The story, which builds with the slow, coiling pleasure of a snake wrapping your ankle, suddenly unspools, hissing into a climax that feels, well, not quite cooked. It’s as if the directors, Beck and Woods (the architects of “A Quiet Place”—with its monsters in the cornfields and its silences screaming for mercy), here trade in their sound design for sermonizing, and only remember, too late, that a fine sermon needs a final, thunderous “Amen.”

But what a middle! The film does a highwire act with its themes, teasing out the slipperiness of control, the uses and abuses of belief, and the need to be guided—even if that guide takes you off the cliff. The dialogue—God, sometimes it sprawls like an overheated op-ed, but right when you’re ready to dismiss it as self-serious, the script bares its teeth. Those scenes between Grant and the missionaries, trading scripture for existential panic, are riveting, like watching Nietzsche argue with a Sunday School teacher mid-exorcism.

Grant is—and this must be said outright—phenomenal. He radiates the peculiar threat of the insidious nice guy; you never know if he’s about to offer you biscuits or slip strychnine in your tea. He plays with cadence, flicks his lines with genteel malice, turning each moment into a guessing game, and suddenly, the audience finds itself hoping for a glimmer of the Grant of old—only to be reminded there’s something far less romantic lurking beneath.

Sophie Thatcher’s Barnes is all sinew and smarts, the kind of heroine who makes you root for survival by sheer force of will—her fear is raw, palpable enough to make you itch. East’s Paxton, trembling and resolute by turns, is her perfect counterpoint; the movie’s tension doubles in the silent spaces between them. You sense genuine terror, not as a cinematic trick but as a cost they’re paying in real time.

The director’s hand here is assured, if sometimes too assured for the good of the film’s heart. The atmosphere all but crawls off the walls—claustrophobic, eerie, teetering on the knife-edge between the rational and the supernatural. It makes “faith” feel like a toxin in the air, crawling under your skin.

And still—there's that ending. After the heady buildup, the film loses its conviction. The conclusion rushes by, clipping the wings of everything it had so painstakingly set up. It’s like being promised revelation and given vague, unsatisfying confession—pie without filling, church without choir.

The film sometimes over-indulges in its own philosophical soliloquizing; some expository stretches sprawl and stall, stretching tension into tedium. But you'll forgive it, I did, because “Heretic” wants to talk to the audience, not just at us—it wants us to leave rubbing our wounds, asking uneasy questions about how easily we surrender our autonomy to a story, a system, or a smooth-talking devil in an Oxford shirt.

You can see the lineage here: echoes of “The Invitation,” “The Witch,” those films that use horror as scalpel, slicing open not just their characters but their audience as well. Beck and Woods have matured past monsters in fields; here the monster is invisible, formed by what we yearn to believe, the pacts we make under duress.

“Heretic” is not perfect, but it is alive. It hustles you up to the altar, asks you to take communion, and then, just when you're ready to be saved, leaves you with crumbs. The disappointment stings because the rest is so good. The ride is exhilarating, the aftertaste bitter—a sermon that loses its voice before the benediction, but you'll remember the music all the same.

You leave wanting more, and that’s no small thing. Would I recommend it? Absolutely—if only to see Hugh Grant trade his halo for horns and make you root, ever so uneasily, for the fall.

“Heretic”—it’s a bruiser, a thinker, a near-masterpiece with a limp. Go, and let yourself be troubled.