After the garish, exhaust-spewing spectacle of most “political” thrillers, Steven Spielberg’s Munich arrives like a shock to the moral system—a slow-burning fever of a film, where triumph is measured not by body counts but by the corrosion of souls. Released in the long winter shadow of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, Munich isn’t content with the easy uplift of righteous action. No, Spielberg has something far more unsettling in mind: he gives us the nightmare of retaliation—personal, national, and ultimately, existential—and then refuses to wake us up.

Drawing from George Jonas’s Vengeance, Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner have stretched a slim thread from the 1972 Munich massacre—a wound that has never scabbed over—into a labyrinth of violence and moral unmooring. It would have been easy to whittle the story down to its pulp roots: Black September’s slaughter of Israeli athletes at the Olympics; the Mossad agents sent roaring across Europe, hunting their adversaries. But Spielberg treats the whole sorry tangle with the grave exactitude of a Talmudic scholar. Each killing isn’t a catharsis—it’s a splinter in the conscience, a shiver that runs down the collective spine of a century spent loving wars for “peace.”

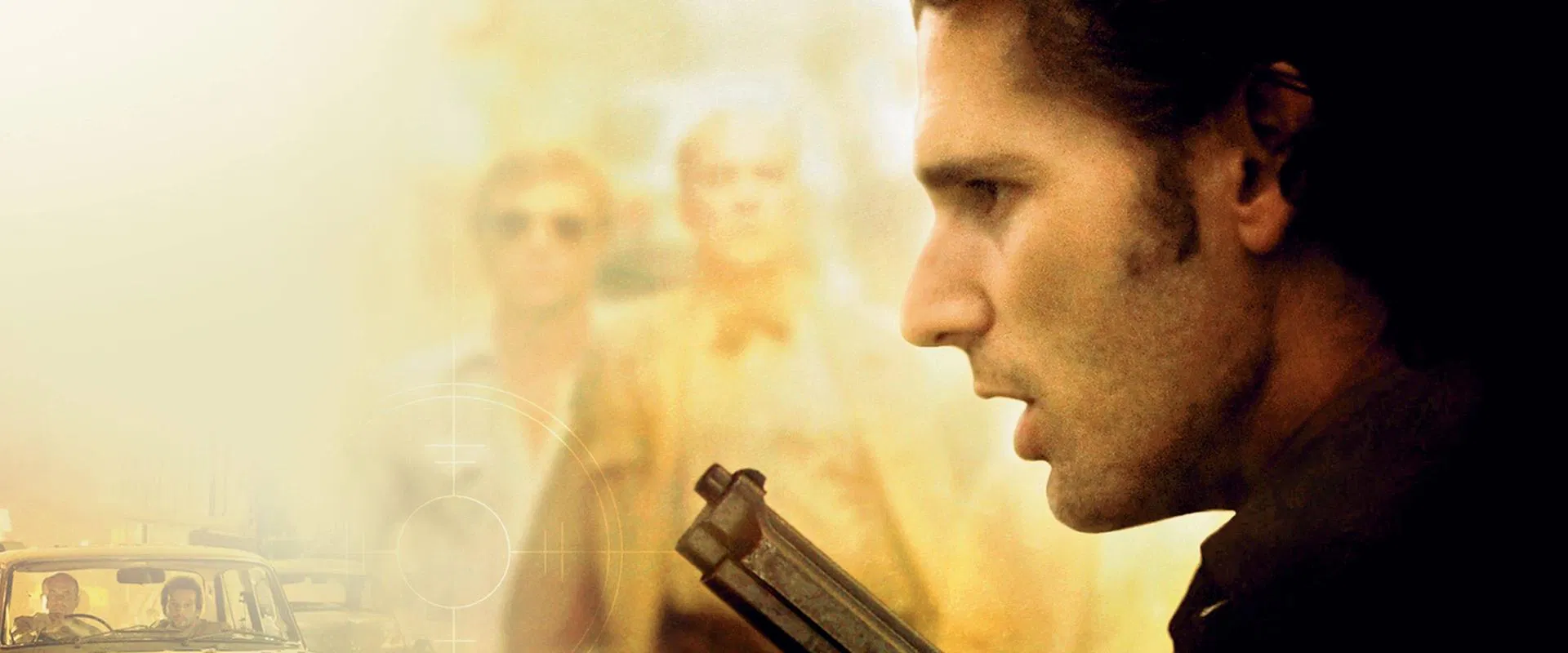

Eric Bana, as Avner, is the film’s battered nerve center. Mossad’s brooding golden boy, he’s tasked with leading his patchwork crew through a campaign of assassinations, exacting a kind of justice that even God might hesitate to mete out. Bana’s performance never tumbles into the easy, lachrymose self-pity you might expect; he imbues Avner with the posture of a man who’s lost his reflection, hunched under the invisible weight of cause and consequence. The missions are collaborative, but each face—Daniel Craig’s staccato bravado, Ciarán Hinds’s flinty reserve, Geoffrey Rush’s watchful, wry handler—registers a different inflection of doubt, exhaustion, or drive. In Spielberg’s hands, these men aren’t action figures, nor are they angels or monsters: they’re repositories for all of history’s bloody fool’s errands.

If Spielberg once risked prettifying horror (see Schindler’s List’s catharses), here he lets the mechanics of murder play out in all their queasy detail. The bombs, the bullets, the nerve-jangling second guesses—they’re choreographed with the precision of a horror film, but the aftermath lingers like a bad taste. Janusz Kamiński’s cinematography slouches from sunlit normalcy—children tumbling on a beach, lovers in dappled apartments—into mortuary blues and grays. The violence, when it comes, is never supersized; it’s the sudden horror of something you can’t undo, and the world doesn’t right itself afterward.

What makes Munich sing, or perhaps snarl, is its insistent refusal to provide comfort. These assassins do not stride through Europe as cleansers of injustice; they sink further into paranoia, moral static, and self-loathing. Spielberg repeatedly frames his characters not as avengers but as casualties of their own mission, men gradually stripped of flags, families, even sleep. The movie’s most brilliant stroke is how it makes the “normal” world—the home, the meal, the chance to break bread—appear faintly obscene compared to the logic of endless reprisal. Even the film’s final gesture, Avner’s invitation to his handler to share a meal in Brooklyn, curdles. Forgiveness is a barricade, not a bridge.

There are lapses. The notorious intercut—sex and slaughter, Avner’s body at cross-purposes with his guilty mind—is Spielberg at his most willfully Freudian, but also at his most tin-eared; the symbolism clangs, distracting us from the far more complex unraveling happening inside Avner’s gaze. Yet even this overreach speaks to the film’s willingness to get lost in the thickets of trauma. Spielberg, usually America’s great orchestrator of catharsis, here sidesteps closure. Each act of revenge is both a howl and a wound, and neither leads to peace.

John Williams’s score hums beneath, a low and sorrowful dirge, refusing to raise the stakes to “epic.” He understands, as Spielberg does, that this story isn’t about victories—it’s about unanswerable losses, the way violence arrives home with your dirty shoes. The Israel-Palestine conflict, so often misrepresented as a contest of martyrs and monsters, is instead seen here as a pitiless circle.

Munich is that rare mainstream American film which not only stares into the abyss, but shows us how we build our homes alongside it. It’s a haunted piece of work, a drama of bone and nerve rather than heroism and bombast, and all the more valuable for its refusals. Spielberg, at last, gives us a historical drama without the easy redemption, demanding that we sit with the consequences—and daring to suggest that history itself is nothing but consequences, rippling out in the shadows, long after the credits roll.