Hellhound is the kind of movie that slips in through the back door of midnight cable and hopes you’re too groggy or forgiving to notice. I wish I could tell you it’s camp, or subversively bad, or even one of those so-bad-you-have-to-write-home-about-it curios, but its ambitions don’t even aim that high. No, this is a film that scrounges at the bottom of the hitman-movie barrel and comes up clutching the genre’s most threadbare clichés like a child rooting through a box of moth-eaten sweaters. It’s a weird little time capsule of every tired assassin-for-one-last-job scenario you thought moviemaking had outgrown, and somehow, it’s still marginally less humiliating than Nicolas Cage’s Bangkok Dangerous—though only just.

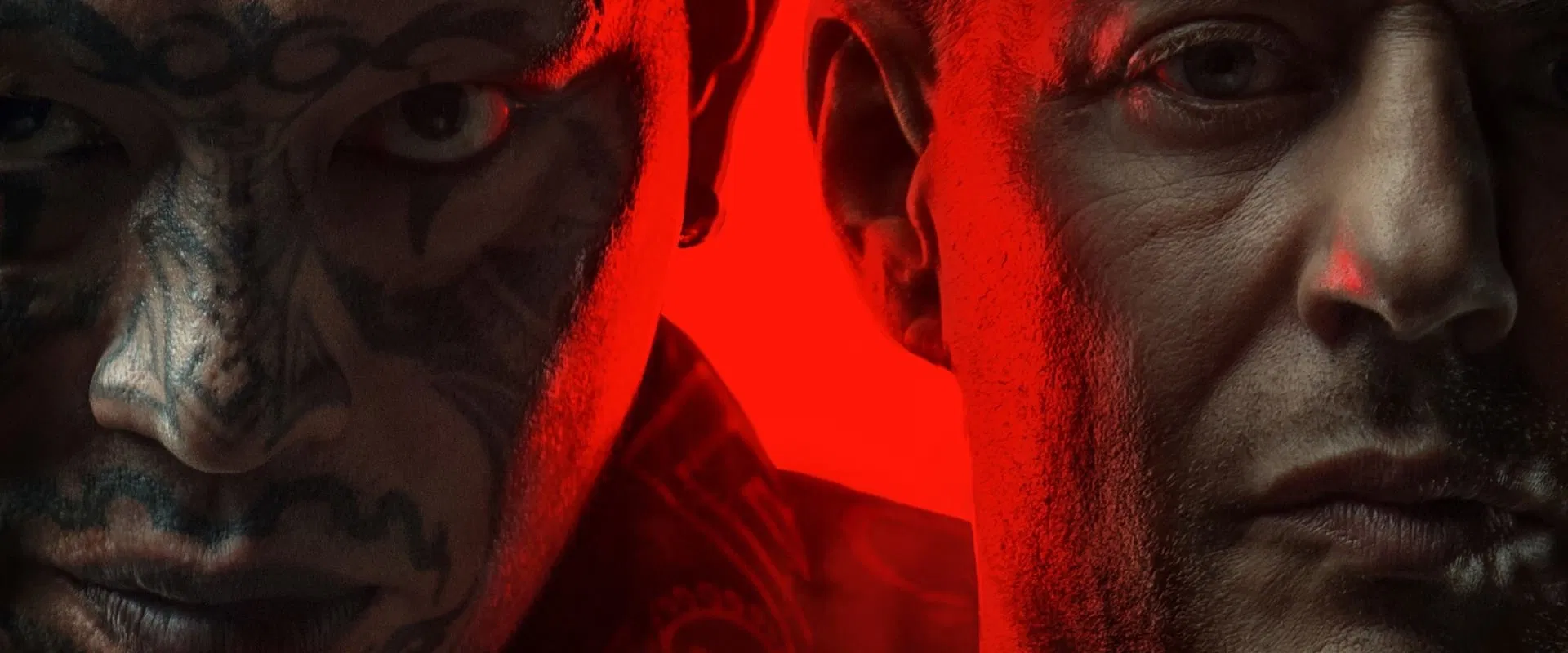

The plot, such as it is, hangs on Louis Mandylor’s Loreno, an aging hitman with a face like a tax auditor and the existential burden of a man who’s checked out of the script’s development process three drafts ago. Mandylor delivers lines with the stony gravity of an actor who suspects the camera crew might unionize if subjected to one more take; entire swaths of character seem to have gone missing in action, perhaps left behind on a bus somewhere in pre-production. His shadow is Vithaya Pansrigarm’s Cetan, a supporting act who wanders through scenes like the ghost of better films, while Van Quattro pops up as Paul—a man whose main achievement is to make you pine for David Carradine’s grandiloquent nonsense, but with none of the tequila warmth or mad charisma. And don’t get me started on Panya Yimmumphai’s Tar: tattooed menace, voice of gravel, all the dread you’d want from a B-movie heavy—if only anyone behind the camera could summon up enough imagination to write him a reason to exist.

Watching Hellhound is a master class in déjà vu. The plot recycles the oldest hitman tropes with such weary obviousness you’d swear the writers were time travelers, carefully avoiding every new idea since John Woo first picked up two pistols. Loreno wants out, gets pulled back in, faces moral choices, spirals into violence. Supposedly, we’re meant to feel the weight of his choices and the cold comfort of professional violence, but you might as well ask an air conditioner to weep. The drama is inert, like a one-way street to nowhere lined with potholes labeled “EMOTIONAL STAKES—SORRY, OUT OF STOCK.”

Now, there are flashes—tiny, stubborn flashes—of something that might have been. The cinematography, bless its heart, tries to invest even the most energy-starved narrative turns with a limp beauty, as if moody neon will atone for lifeless dialogue. And oh yes, the action. Somewhere beneath the layers of dross, the stunt team produced a few kinetic set pieces that wake you from the film’s slumber with a jolt, only to be let down when the script arrives to club you back into insensibility. Take, for example, the moment when Paul, in a bout of accidental wit, tells his own bodyguard to call a doctor for the dying driver only to get, “It’s late. Doctor Sleep.”—the kind of anti-joke that suggests David Mamet got drunk and started texting dialogue prompts at 2 a.m. It’s rare you find a gangster movie so committed to slapstick idiocy that you want to congratulate it for honesty, if not for sense.

The fight scenes earn a modest gold star in a sea of failing grades. Choreographed with enough panache to briefly fool you into thinking you’re watching a reel from a vastly better film, these moments jab the narrative with the only hints of pulse its creators can muster. But stacked against the hollowed-out characters, it’s like finding a diamond earring in a landfill: you’re too distracted by the stench to care.

Then comes Tar’s ending—the movie’s grand attempt at “poetic justice,” which instead lands with all the gravitas of a wet sock. He’s built up as the resident monster, face tattooed, threatening to burn through the screen. Surely, you think, his climactic moment will at least produce some perversely memorable sendoff? Instead, what we get is a dramatic showdown so limp, so drooping with lost potential, it seems the filmmakers simply lobbed a coin and shouted “Whatever’s easier!” across the set. His boyfriend crashes in for a finale that’s meant to jolt us awake—maybe even move us—but the whole thing is about as affecting as a public service announcement for wet paint. By the time credits roll, you can only wonder if anyone involved believed in “poetic justice,” or simply cribbed it from a Wikipedia summary during their lunch break.

Hellhound is the cinematic equivalent of spam email: so generic, so devoid of personality, so bafflingly bland in its recitation of the rules of the genre that you half-suspect it was penned by a particularly bored artificial intelligence. The dialogue lands with the tinny clang of Xeroxed catchphrases, character arcs appear to have been copy-pasted from films whose only redeeming feature was existing first, and the so-called “twist” arrives like a last call at a seedy bar: sudden, unwelcome, faintly nauseating. You stagger out less entertained than existentially troubled—“Why did I watch this? Do I really deserve this punishment?”

If there’s a lesson in Hellhound, it’s that badness is not merely the absence of art, but the presence of every bad idea you’ve seen before, reheated, and served without seasoning. In the end, you are left stranded—caught between the comic and the catastrophic, shaking your head in disbelief. If you find yourself in front of this film, don’t say you weren’t warned. You might even find yourself questioning not just the movie, but all your life choices that led you to this point. In a world abounding with brilliance, why treat yourself to cinematic cat litter?