There’s something bracingly cold in the Korean morning after, and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance unspools as if Park Chan-wook had gathered up every post-war trauma, every splintered family, and boiled them down to their reasonless elemental grudge. If the opening salvo to the so-called “Vengeance Trilogy” feels like an autopsy of the revenge thriller, it’s only because Park is dissecting not just genre, but the black, sodden heart of the human condition itself. How often do we watch films about vengeance and walk out, buoyed by the giddiness of catharsis? Not here. Here, you stagger out like you’ve come from a wake, the taste of rust clinging to your tongue.

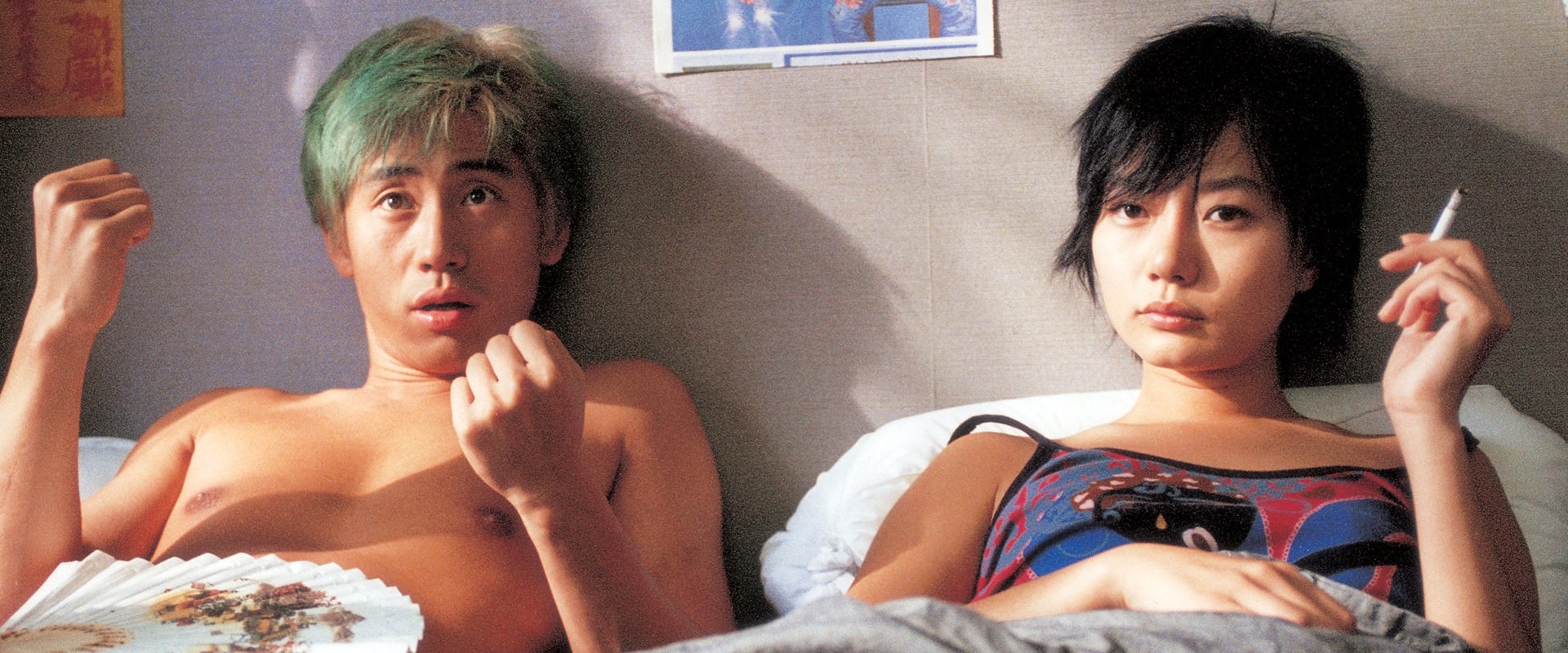

The premise, if you could scribble it on a bar napkin, is pathologically simple: Ryu, a deaf-mute factory worker (Shin Ha-kyun—so delicately opaque he feels sculpted from grief), stumbles into a kidnapping scheme intended to save his ailing sister, only to see it curdle into tragedy. That’s the easy part. The real marvel—and anguish—is in how Park so meticulously builds a world out of casualties, refusing to draw the comfort lines between villain and victim. Song Kang-ho’s Park Dong-jin is the sacred monster opposite Ryu: a father wrung out with anguish, transformed into an engine of retribution, as terrifying and pitiable as anyone since Michael Corleone lost his shine. And then there’s Bae Doona as Cha Yeong-mi, dancing on the anarchic edge, injecting a charge of chaos into an already ruinous spiral. Is this trio meant to make us choose sides? Park, that sly manipulator, tricks us into caring for everyone—and then punishes our sentimentality with every new twist of the knife.

What unsettles is not merely the bleakness—though, make no mistake, the bleakness is as dense as a concrete block—but the refusal of any easy answers. Who is the victim here? Who is pure? Park dares you to find even one untarnished soul (good luck—the screen is so smudged you’d need lye to wipe it clean). The film’s moral calculus is so perverse it almost becomes liberating: vengeance is neither redemptive nor even satisfying, just another form of spiritual entropy.

You can feel Park’s hand in every composition—how he and cinematographer Kim Byeong-il calibrate each frame so that even desolate industrial spaces crackle with a kind of wounded beauty. The sparseness holds your eye—would-be grandeur stripped bare, the violence erupting in spaces so ordinary, you almost don’t notice until it’s too late. The sound design, too, is so judicious that when any music does creep in, it’s like a shiver—reminding us that these are not superheroes, but the damned sawing through the silence of their own regret.

A word on pace: you won’t find the caffeinated joys of a studio thriller here. The first hour crawls—deliberate, exacting, the narrative stretching out in slow, brackish pools of dread. Some will squirm. But it’s just Park tenderizing your nerves, so when the hammer finally comes down, the violence is intimate and personal—a crimson echo rather than a gorefest. Some will say it’s “restrained,” but that misses the point: the movie is not about the spectacle of pain, but about pain itself, refracted through the murky morality of those who can’t escape its orbit.

And yet, the performances shimmer—Song Kang-ho wrenching dignity from despair, Shin Ha-kyun an open wound stitched shut by necessity. Park doesn’t direct his actors so much as dare them: here, in this skin, can you make us bleed too? They do. You will.

The film is good—almost too good. If it falters, it’s in the unrelieved grimness; you begin to wonder if Park ever smiled in his life, or if his only joy is in watching audiences twist in their seats. But there’s genius here—in how each character’s arc becomes a circle, folding back on itself until everyone is howling with grief and rage and nobody remembers who threw the first stone.

In the end, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance is that rare beast, a revenge story where vengeance is neither justice nor salvation, only another rung on the wheel of suffering. Park forces us to reckon with what lies beneath our appetites for cinematic bloodshed—a reminder that in the final calculation, the worm turns, and vengeance is only another word for misery, handed down like a family heirloom.

You don’t watch this movie to be entertained; you watch it to be indicted. It’s misery as meditation—and a bruised valentine from a country that has learned, painfully, how easily goodness can be wrung out of the soul. Are you a cinephile with any claim to seriousness? Then see it. Park casts a harsh light, but sometimes, that’s the only way to see what’s really there.