Sometimes a movie unspools with the comforting hum of déjà vu—a story you know by heart even as the unfamiliar faces of another country’s cinema strut and stumble before you. Monga, directed by Doze Niu, is that kind of film, a Taiwanese gangster saga that aches to be muscle and poetry both, splashing its neon lights across Taipei like it’s trying to reinvent the shadows themselves. As the camera drifts through the back alleys and discos of 1980s Wanhua, you recognize the ritual: we’re being asked to believe in brotherhood carved out of bruises and blood, loyalty and its slow rot. And I was ready—I wanted the sweet, sickly rush of a genre picture that tilts toward heartbreak.

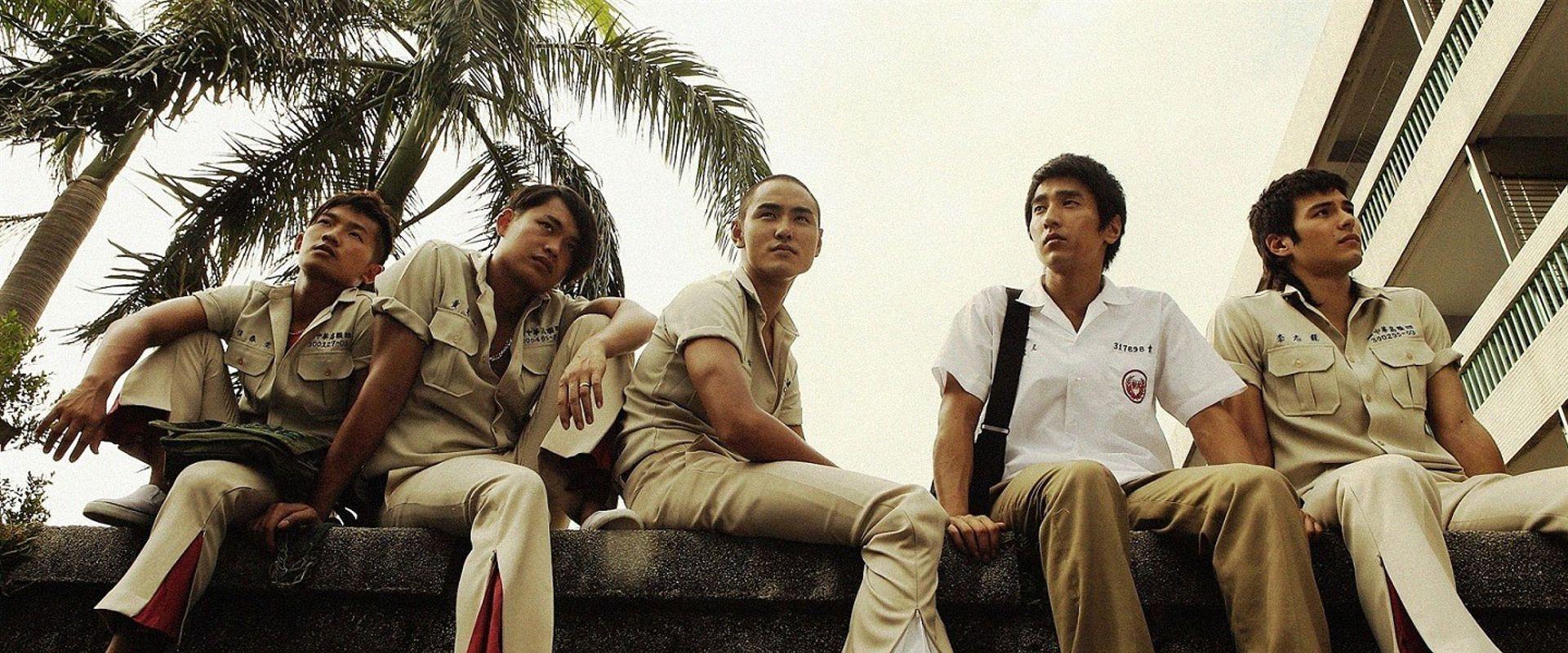

Doze Niu, more craftsman than radical, leans into the humid mythos of coming-of-age-in-a-gang. Young Mosquito (Mark Chao) arrives as a bullied blank slate; a few scrappy fists later, he’s scooped up into the thick testosterone stew simmering through the film’s first act. The boys—led by Rhydian Vaughan’s Dragon and Ethan Juan’s Monk—circle him, half-wary and quick with camaraderie. There’s a delayed, almost theatrical reveal of the film’s title some 20 minutes in, as if Niu is daring the audience to commit to the drama before he's ready to put his brand on the picture. Did I squirm? Maybe a little. But there’s pleasure in seeing a director trust in his slow burn, at least at first.

Yet if you’ve attended the cinema church of Scorsese, or even the hyper-stylized Hong Kong epics of triad lore, you might feel the familiar chords vibrating from the moment Mosquito’s knuckles are bloodied. Betrayal, rivalry, the cruel arithmetic of “family”—Monga wants to excavate why gangs decay from within, but it mostly just traces the wear patterns. The betrayals here thud like predictable dominoes. I waited for the film to dig deeper, to ask why these boys cling so hungrily to each other, why loyalty sours to violence. Instead, it’s content to let the genre do the heavy lifting, satisfied with being good enough, never quite dancing past its own outline.

But if the narrative is only intermittently alive, the cast is the furnace that powers what’s vital in Monga. Mark Chao’s Mosquito grows from puppyish and raw to a man battered by survival—a transformation that touches something tender, if a bit formulaic, at the film’s bruised heart. Ethan Juan’s Monk, though, is the one who earns his stripes: a thinker forced to navigate the gang’s moral debris, who speaks with his eyes when the script gives him nothing to say. His pain, his calculation, are the moments when Monga vibrates with real feeling—the kind you can’t fake with slow-motion struts or slo-mo gunfire. In contrast, some of the supporting players (the clownish A-po, especially) seem less like people and more like industry-mandated comic ballast, there to break the tension because someone in marketing demanded a laugh. Dog Boy, the bad-dog antagonist, gnashes his teeth but doesn’t inspire a nightmare. When the movie needs fangs, he delivers only a bark.

Directorially, Niu is nothing if not earnest; Monga looks handsome, its 1980s palette splashed with the requisite nostalgia, but the violence is too clean, the blood almost perfumed. This is a film petrified by its own prettiness, unsure whether to snap or caress. The pacing, too, wobbles. The movie spends so long arranging its pieces—hell, the prologue practically stretches on like a lover afraid to let go—that when the gears of betrayal finally grind into place, the tension is muted. We’re meant to ache as friendships are shredded, but the punches land like air.

And yet: give the film credit for seeing brotherhood as both haven and hell. The emotional current at its core—the friendships that bloom and wilt, the way the illusion of loyalty can drop out from under you like a trapdoor—that lingers, however faintly. In the end, Monga is less a thriller than a melancholy coming-of-age—more interested in sighs than gunshots. You come hoping for thunder, but what you get is drizzle.

Cinephiles might point you toward Young and Dangerous or The Godfather as blueprints for this kind of story, and they’re right to. But Monga doesn’t have the buoyancy, the Shakespearean sweep or psychosexual violence of those films; it students the genre instead of redefining it. What it offers, instead, is a Taiwanese flavor—a homegrown ache—and that, for all its hesitation, makes it worth a visit.

Still, as the credits rolled and the screen bled into black, I was left with more unfinished business than catharsis. The supposed climax barely registers, and the film’s coda feels like a dare with no punchline—a dust cloud where you want a wound. Is being “good” enough? Sometimes you want a gangster flick to cut you deeper, or at least leave behind a scar.

In sum: Monga is an affectionate, tangled ode to boyhood and betrayal—solid, but more an echo than a revelation. Its emotional register is genuine, even as the plot paces in well-worn circles. For those willing to spend two hours down these violent, moody Taipei streets, there’s enough heart to be found—even if, as with gang life itself, you walk away wishing for a little more blood in the water.