If the movies have always been a kind of fever-dream export, then “Brother” is Takeshi Kitano’s midnight shipment—an East-meets-West yakuza odyssey dipped in Los Angeles neon, redolent with the sweet jasmine of gunpowder. Here’s a gangster film that grinds its teeth on the concrete of two cultures, where ritual silence means as much as spilled blood, and loyalty is currency spent and spent again. It’s a picture that, for better and occasionally for worse, gleams with the eccentric fingerprints of Kitano—who, with a gaze as blank as a shut safe and an enigmatic half-smile, turns the genre inside out until the expected comes out looking like a magician’s trick you can’t quite catch.

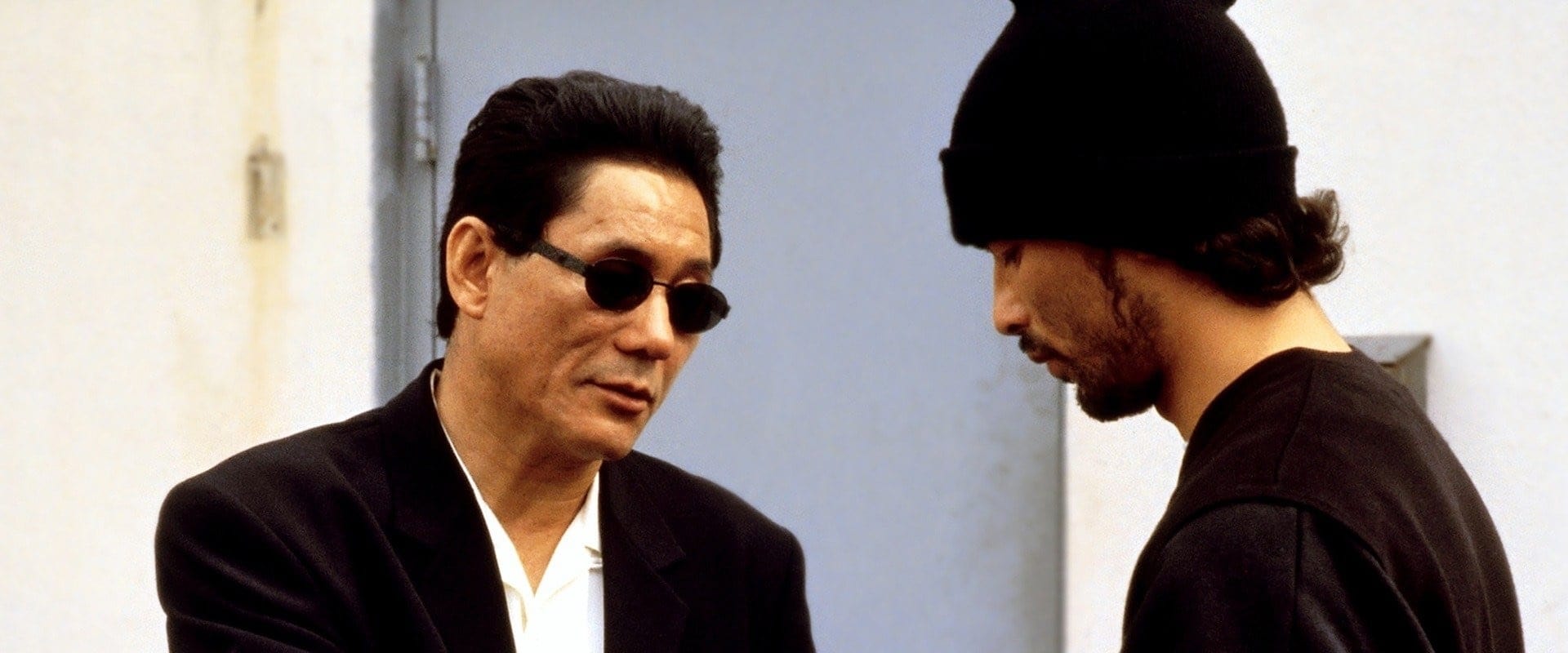

In “Brother,” Kitano's Yamamoto is less the usual cinematic tough—no swagger, no grandstanding, and certainly no embarrassment of emotional confessions. Instead, there’s that infamous impassivity, his face shielded by shades and that sly, half-winking smile. Kitano, importing his own mythos as Beat Takeshi, stalks through California as if he owns some secret patent on the concept of cool. And the violence? Sudden, unadorned, and never set to the moralizing hum of Hollywood’s redemption machine. Yamamoto doesn’t lecture or weep for his crimes; he just survives, sometimes by sheer indifference. When he lands in LA, fuses with his half-brother Ken (Claude Maki), and gathers a motley crew under his icy wing—including the kinetic Denny (Omar Epps)—Brother sketches out an oddball family, bound more by necessity than sentiment. There’s a strange, understated tenderness under the armor—flickering like a defective neon light in a hotel lobby at midnight.

The film spikes with moments that ought to be jarring—and often are: awkward silences, gnomic dialogue, American actors fumbling their way through Kitano’s Bizarro-zen pacing. Critics might call some of these moments “misfires”—and they're not wrong about the limp jokes or the bellboy’s Calvin Klein-commercial line readings that threaten to drag the mood into unintentional comedy—but if you’re open to it, that’s part of the art. Kitano refuses to translate his odd rhythms into Hollywood English. The result is something that sometimes baffles and sometimes electrifies, but never feels like a product. If anything, Brother is the anti-product: a film with a shiner on its cheek and blood on its knuckles, content to make mainstream audiences uncomfortable.

And the performances? Kitano is a force-field at the film’s center, pulling everything into, then freezing it at, his speed. Omar Epps, meanwhile, gives Denny a streetwise tactility—a mix of suspicion and yearning—that flares every time he shares the screen with Kitano. Their uneasy bond is the movie’s heart. Claude Maki’s Ken hovers in the shadowlands between admiration and insecurity, a little outclassed but, for the most part, believable. But the rest of the ensemble? Let’s just say the supporting cast moonlights as a cavalcade of beautiful, clunky extras—some genuinely interesting (Masaya Kato as Shirase imbuing Tokyo’s criminal underworld with a prickly edge), some leaving you wondering if they wandered in off a soap opera set one street over. When an actor turns what should be a mean-streets moment into slapstick, you wince and move on—Kitano, unfazed, just lights his cigarette.

Still, there’s a minor miracle buried under all that LA strangeness: Brother is studded with the fresh faces of tomorrow’s Hollywood rogues gallery. Omar Epps, perched on the threshold of stardom. A slice of “Hey, it’s that guy!” material courtesy of a baby-faced Noel Guglielmi. Even the brief, soon-forgotten appearances feel oddly charged in retrospect—Kitano seems to have a clairvoyant’s eye for talent wandering in from the cold.

Visually, Kitano paints LA with his usual minimalist brush—the camera lingers, then erupts, cutting like a switchblade from silence to carnage. There’s no ornamental sadism, no painterly blood ballet; when violence comes, it’s sharp and almost anticlimactic. Yamamoto’s world-weary pragmatism, and Kitano’s gift for stretching tension past its breaking point—all of it works to make the film less an opera and more a brittle, dissonant poem scratched on a motel wall.

If “Brother” stumbles, it’s at the crossroads of two cinematic planets. The dialogue sometimes clangs, the LA cast can’t quite catch Beat Takeshi’s lunar gravity, and a few scenes verge on clumsy parody. Yet even these failings are spirited—flaws in the glass, proof that it’s hand-blown, not extruded on an assembly line. Kitano’s refusal to serve his genre straight is precisely what makes the film so haunting. He gives you brotherhood and carnage, codes and cultures colliding, swagger and melancholy jostling for space on cold Los Angeles streets.

In the end, Kitano’s “Brother” is a strange, memorable, fiercely distinctive gangster elegy—an echo chamber of silence and violence that works best when it lets you breathe the California smog between gunshots. It’s a picture that lures you out of your hermetically sealed expectations, then skews the world until the only thing left is Kitano’s inimitable signature: the elegant brutality of making you care, almost despite yourself. You don’t walk away from this movie feeling clean or uplifted, but you might find yourself haunted by that impassive smile—and the darkness it conceals.