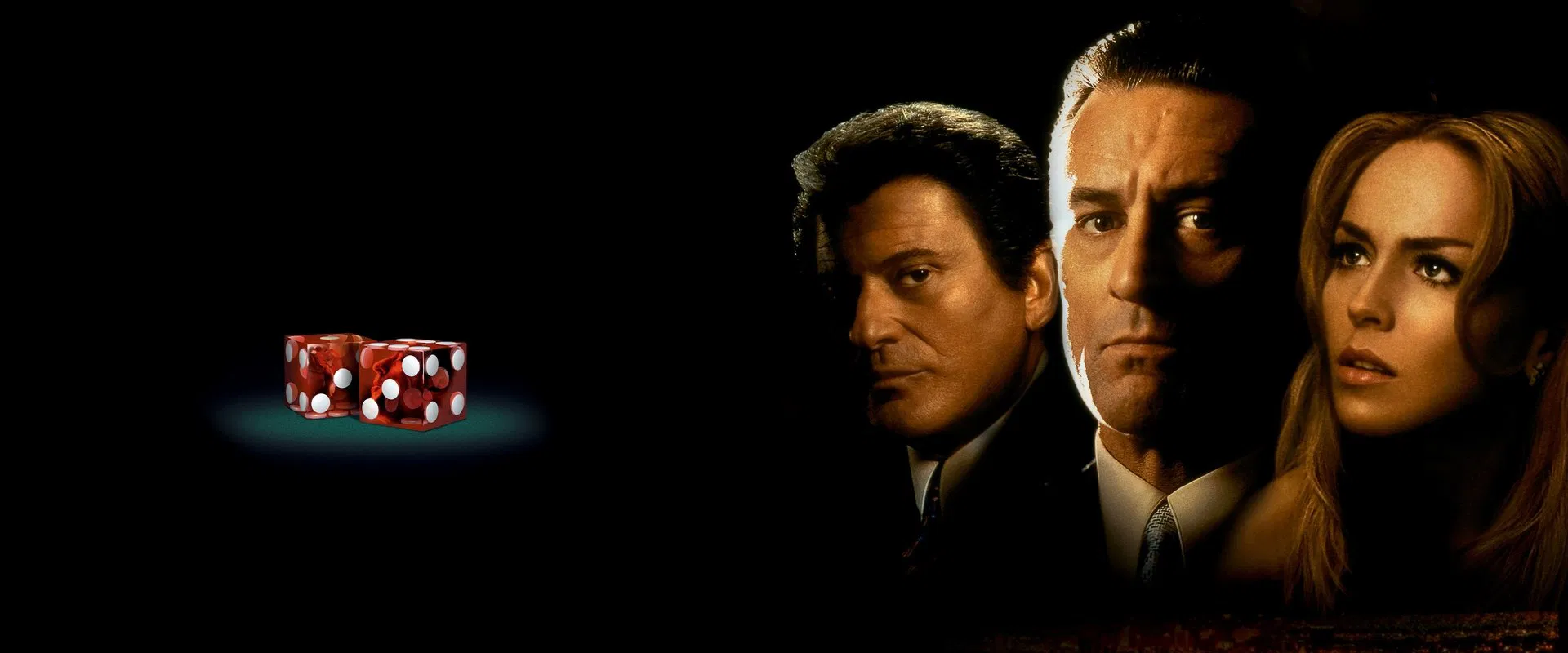

Say what you will about Martin Scorsese, the man can squeeze new blood from a dead body, even when that corpse is the gangster film itself. With Casino, he revisits the operatic, violence-soaked terrain so memorably realized in Goodfellas. But this is no mere retread. Here, in the sun-baked, gaudy playground of Las Vegas, Scorsese paints with brighter neons and darker shadows, as if the moral decay is more lurid for being so thoroughly lacquered in gold. And, confession time, this is the one that tops my list, staking a claim even above Goodfellas in the Scorsese firmament.

It’s been said, perhaps in apocryphal, cinephile circles, that Casino holds the record for most dialogue in a movie. If it’s true, it’s a record worth setting. The narration pours over the screen in torrents: figures hustling, scheming, loving, and betraying, everyone telling their side with the assurance of a poker shark. And yet, for all its relentless exposition, I never found myself wishing for quiet. If anything, De Niro’s Sam “Ace” Rothstein could wheel and deal his way around casino tables for ten hours and I’d lap it up. Joe Pesci’s Nicky Santoro, by turns loyal muscle and rabid dog, matches him twitch for twitch, firing off lines so fast and furious they could leave bullet holes in the upholstery of the Tangiers’ lobby. Together, they’re a two-man roman candle act, charisma and danger entwined.

Scorsese begins in familiar territory: the real-life chronicle of mobsters muscling their way into Vegas, the last American frontier waving its gaudy banners and stacked chips. What’s surprising is how the film manages, at every turn, to strip away our illusions about glamour and risk. Yes, we’ve all heard the sermon about gambling’s perils, but Casino digs deeper into the house’s machinery, the gears, the skimmers, the way cheaters are sniffed out and dealt with a clinical, unblinking brutality. There’s a sequence here that should be mandatory viewing for anyone with delusions about beating the system: Ace, the king of cool, catching a pair of amateur Morse-code tricksters with a ruthlessness that’s as bracing as a glass of iced gin. The film’s message chimes through: the tables may be velvet, but the violence is real.

Yet Casino isn’t just a fail-safe how-not-to guide for small-time grifters; at its heart, it’s a feverish, operatic tale of loyalty curdling into paranoia, love souring into pure acid. Sam, outwardly the perfect professional, has a soft underbelly—call it affection, or just plain hubris—exquisitely exposed by Sharon Stone’s Ginger. Stone’s performance, shrill as shattered crystal and just as shattering, is the film’s wicked wild card. You sense, from the start, that Sam’s marriage to Ginger is doomed, but the gradual, messy spiral—from diamond-wrapped hustler to desperate, drug-addled siren—retains a perverse, operatic grandeur. Hers is the classic American tragedy: seduced by success, destroyed by it, doomed to love men—De Niro and, in a brilliantly sleazeball turn, James Woods’s Lester—who are themselves enslaved to their appetites.

And then there’s Pesci. Nicky Santoro is the sort of mobster who seems to vibrate right out of his own skin—pure, short-fuse volatility. These are not the cartoonish outbursts of a less knowing film; Scorsese grounds every act of violence in character, making the infamous “cowboy” scene (has any movie ever made an argument for proper table manners more brutally?) a kind of twisted morality play. Nicky claims to protect Sam, but his rampages—hilarious, terrifying, and, eventually, tragic—form the centrifugal chaos that scatters friend and foe alike. By the time of his grisly fate—one of Scorsese’s all-time pitiless payoffs—the only real surprise is how inevitable it all feels. Order may be an illusion; Vegas just lets the chaos play longer.

Scorsese’s style is riotous and dazzling, but also precise. The camera slides through counting rooms, skims over desert roads, ducks into club booths. The music cues—Paul Anka, The Stones, it’s all here—give the film a kind of garish glitter, as exhilarating as a $50,000 roll of the dice. But it’s the film’s structure—like a confessional fever dream, with interweaving voiceovers, flashbacks, and those devastating, omniscient reminders of what will happen to every doomed operator in this world—that lends Casino its sweep. The narration, which might have been pedantic in lesser hands, here feels conspiratorial, sly, and mesmerizing. It’s as though we, the audience, are the ones being coached through a grand heist, only to realize we’re being fleeced along with everyone else.

If the film has a true subject, it isn’t just the mechanics of skimming or the mob’s old-school punch, but the perverse magic of the American dream curdled into the American scam. The mob didn’t destroy Vegas—the corporations did, sterilizing sin into a family-friendly package of buffets and blinking slot machines. Sam ends the film amid the sanitized rot of a new era, still a survivor but forever exiled from the real action. Here is Scorsese’s bleak joke: The mobsters might be dead or buried in cornfields, but at least their Vegas was honest about its corruption.

For me, Casino isn’t just another cautionary tale. It’s a wild, irresistible carousel ride—the sort that leaves you dizzy, dazzled, and just a little afraid to step off. Scorsese, De Niro, Pesci, and Stone gamble big, and the payoff—emotional, visceral, and cinematic—is the jackpot. If you’re tempted to wager, heed this final warning: the house never loses. And Scorsese remains, once and for all, the house.