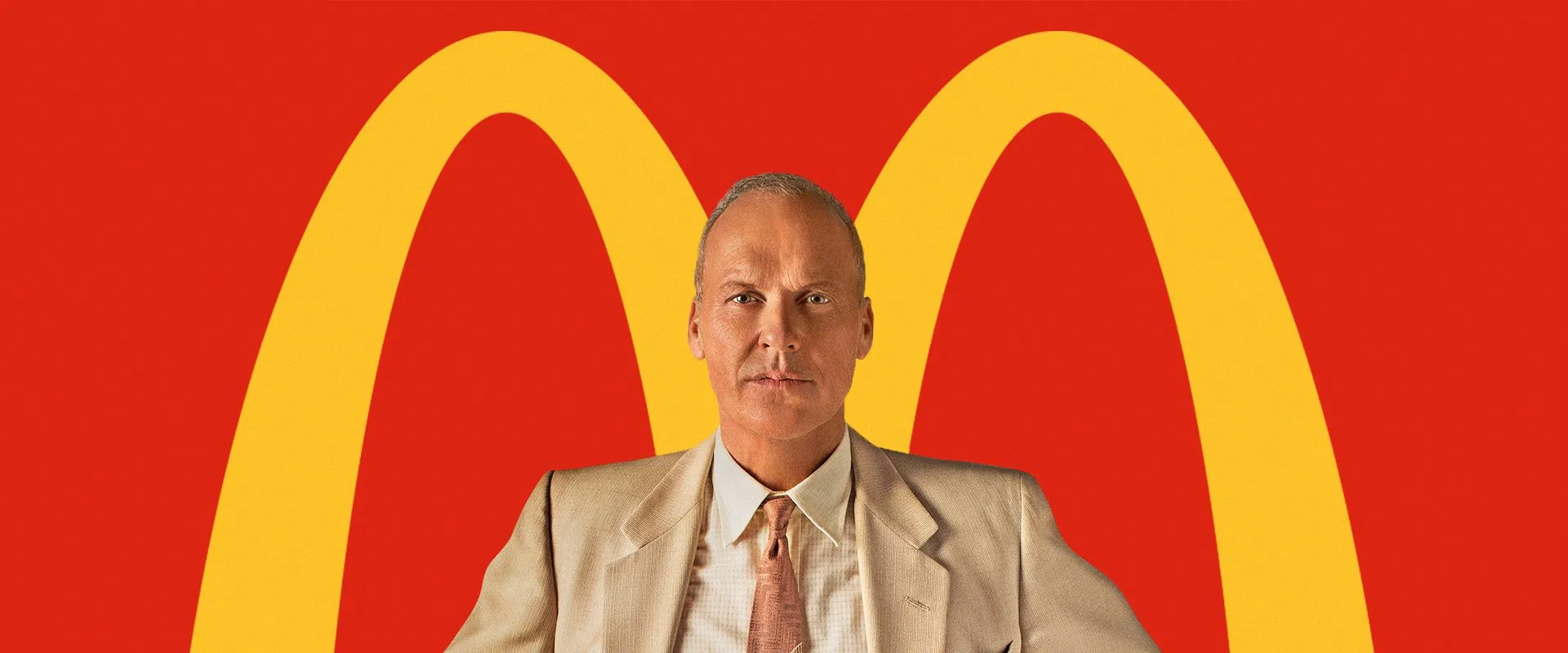

The first jolt of The Founder isn’t the sizzle of a burger hitting the griddle; it’s the smack of Michael Keaton walking into the frame like capitalism’s answer to a grinning shark. Keaton, who’s been on a late-career tear ever since Birdman, doesn’t merely play Ray Kroc; he seems to inhale him, then exhale an all-American fog of hustle, charm, and predation. If Daniel Day-Lewis gave us petroleum-slick ambition in There Will Be Blood and Jesse Eisenberg did the hoodie-clad math in The Social Network, Keaton supplies the ketchup-red swagger: a salesman’s smile that curdles, scene by scene, into something closer to manifest destiny with a milkshake machine.

What’s so perversely engaging about John Lee Hancock’s picture is how tidily it organizes the American Dream into an assembly line of betrayals. The director, never one for stylistic fireworks, turns restraint into a kind of slow burn; he lets Robert Siegel’s sinewy script do the flashing while he keeps the camera pinned to the choreography of money changing hands. Everything is functional, efficient, like those stainless-steel counters the McDonald brothers invented, and that very neatness becomes the film’s moral needle: every time the grease pops, you feel a pang.

And what a pair of brothers. Nick Offerman’s Richard (mustache quivering with wounded integrity) and John Carroll Lynch’s Maurice (all big-brother warmth curdling into disbelief) give the movie its bruised heart. These two play the McDonalds as gentle engineers of an ideal, quality over quantity, order over chaos, until Keaton’s Kroc turns up, nostrils flaring, sniffing out limitless expansion. Watching Offerman’s flinty pragmatism and Lynch’s open-faced decency collide with Keaton’s ravenous grin is like watching a Calder mobile sway above a buzzsaw.

The pleasure, yes, pleasure, of the film is that it refuses to sand the edges off its central figure. Kroc’s real-life hijacking of a family business is devastating, yet The Founder allows him cunning flashes of humanity. There’s that scene in the middle distance, the salesman alone in a motel room, listening to a motivational record skip, an echo chamber of his own longing. We glimpse desperation under the bravado, and for a moment you almost root for him. Then the next handshake curdles, the next contract is flavored with powdered milkshake mix, and the movie reminds you that a dog-eat-dog world ends with blood on the linoleum.

Hancock’s filmmaking rarely calls attention to itself, but the period detail is scrupulous (you can practically taste the Formica), and the pacing is uncluttered: each franchise sign sprouting up like a mile-marker on the road to moral erosion. Carter Burwell’s score hums along like an industrious drill sergeant, goading the narrative forward, even as your sympathy slides irrevocably toward the brothers abandoned at the curb.

Keaton, though, is the motor. His Ray Kroc moves through the picture with the springy menace of a man who’s already imagined the billboard bearing his name. The moment he changes “Prince Castle Salesman” on his business card to “McDonald’s Corporation”, you can feel the air tighten. Awards bodies love “transformations,” but here the fireworks come from the actor subtracting, not adding: he pares himself down to pure appetite. It’s one of those performances that turns a biography into an X-ray.

For all its corporate pageantry, The Founder is finally a character study, a portrait painted in mustard yellow and moral gray. It’s sad, even faintly tragic: the brothers left with a ghost sign over a shuttered restaurant, the handshake royalty that never arrives. Yet the film doesn’t wallow. It plants you squarely in the paradox we all live with: McDonald’s may hawk junk food, but it also feeds one percent of the planet every day. We dislike the taste, perhaps, but the line at the drive-thru winds on.

By the time Keaton’s Kroc is plagiarizing self-help homilies for a speech that will kick-start the next epoch of expansion, the movie has sold us something, too: the queasy exhilaration of watching the American Dream devour its dreamers. You stagger out entertained, informed, and a little heartsick, exactly the price of that extra-value meal.

In the end, The Founder is as sleek and efficient as the empire it dissects, only it serves its burgers with a side of conscience. You’ll never look at the Golden Arches quite the same way again, and you may never find Michael Keaton in there, either: he’s disappeared into Ray Kroc’s grin, and the echo of that grin lingers, like the smell of fries you’re ashamed to admit still make your mouth water.