Let’s mark STRAW’s arrival on the Netflix scroll not as a quiet debut but with the thudding, dissonant crash of a fire alarm, one of those pulpy, middle-of-the-night interruptions you half resent and won’t soon forget. This is Tyler Perry pushing melodrama to the edge of the precinct, a kitchen-sink-pressure-cooker tragedy with more indignities than a daytime soap marathon, yet fierce enough in its final moments to repay (if not quite justify) the ordeal. It’s equal parts a how-bad-can-it-get gauntlet and a surprisingly alive, wounded scream from the cracked ribcage of America’s social machinery.

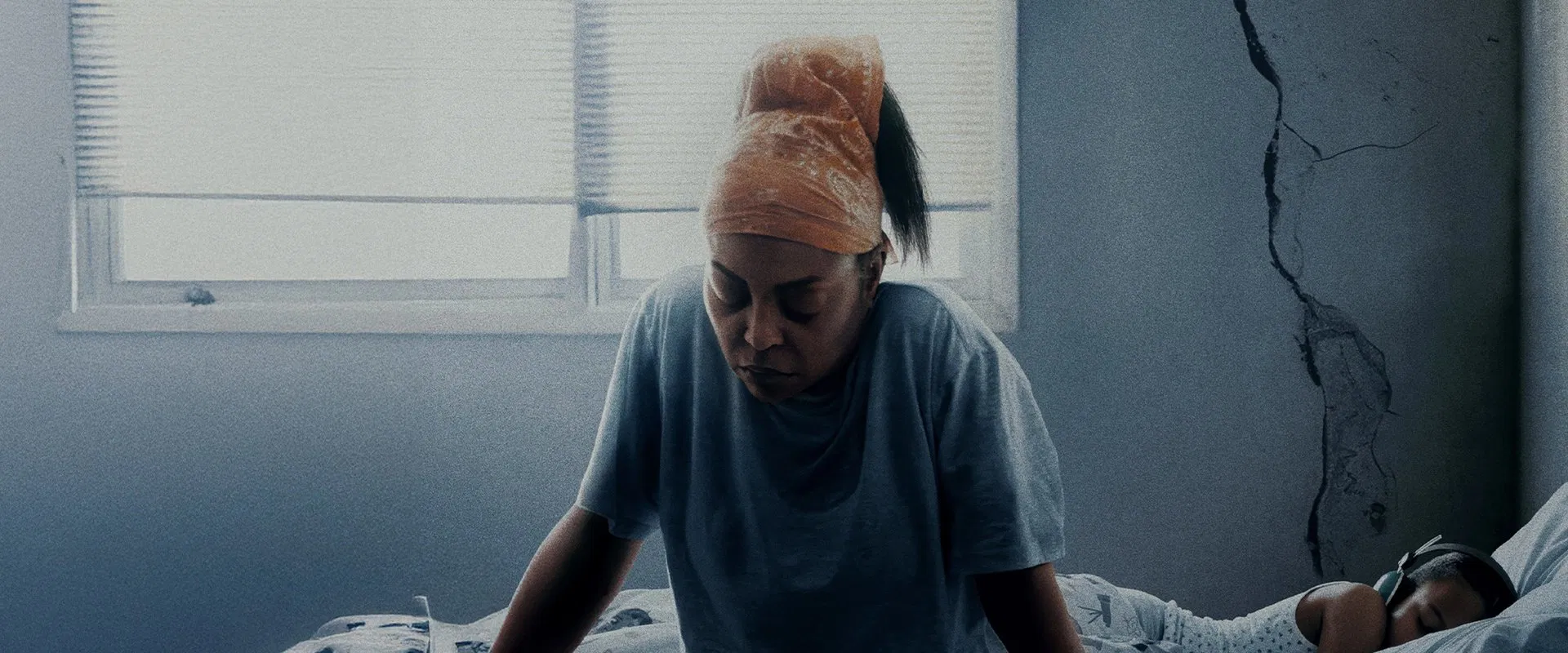

Taraji P. Henson, so often underutilized or trapped in glossier roles, carries the burden here as if she’s hauling the debris from ten other melodramas on her back. She gives a performance with enough raw voltage to burn through Perry’s metaphorical plywood, so ferocious in her breakdowns, so unvarnished in her fury, that you begin to forgive the script’s love of ruin. When she shouts into the vacuum, nobody ever helps me, you hear not only the lament of her character, Janiyah, but the keening whine of a filmmaker who has always preferred struggle writ large and subtlety left offscreen.

The first half is methodical in its miseries: a series of Chekhovian calamities, each shot framed as if shrugging, “Well, what did you expect?”, eviction before lunch, pink slips with a side of bottled milk, cops who twirl their malice like silent-era villains, and a parade of bad luck so maximal it’s almost comedic. Perry never met a conflict he wouldn’t double, it isn’t enough for Janiyah to be harassed by a cop, he has to be off-duty and vengeful, for God’s sake! Only here, life comes at you fast and in quick succession, until banality slips into nightmare and every everyday encounter becomes suspiciously laced with doom.

Were it not for Henson, all this might buckle under its own lugubrious weight. But Perry, to his credit, lets her run at the camera with the kind of unpolished, skin-flaying emotion that most contemporary dramas anesthetize. Audiences, those hardy souls who endured the first hour’s barrage, might debate whether her wide-eyed mania occasionally tips into excess. (I suspect that depends largely on whether you believe breakdowns are best played in minor chords or shouted until your throat is raw.)

The film’s shift into thriller territory lands with a jolt, almost as if Perry, restless with piling on everyday indignities, suddenly tossed his protagonist into a new, more dangerous arena just to see what she’d do next. What’s genuinely impressive is how, by the time the ending arrives, the film manages a kind of emotional sleight-of-hand: it gathers your anxieties, flips your expectations, and delivers an impact that lingers long after the credits. The final revelation doesn’t just reframe what’s come before; it transforms the story’s suffering into something stranger, more ambiguous, and, for a brief and startling moment, truly resonant. There’s a haunted aftertaste, a need to revisit earlier scenes, picking through the debris for missed clues and new meanings.

Perry’s touch for nuance remains as blunt as a gavel. The “bad cop” isn’t so much written as rubber-stamped; the supportive detective (Teyana Taylor, as luminous and unflappable as her makeup team will allow) looks like she wandered in from an upper-midrange fashion ad. There’s not a lick of subtlety in the costuming, and every minor role seems engineered for maximum message-delivery. But none of this fatally wounds the experience because Perry isn’t aiming for realism, he’s staging an allegory with the sledgehammer force of a Greek chorus.

My qualms, inelegant story beats, supporting cast delivered with all the nuance of a town hall, are nevertheless outweighed by the blasted emotional clarity of Henson’s, and occasionally Shepherd’s, work. When melodrama is this unashamed, it sometimes turns cathartic by accident. And though you might wish for a less schematic brand of suffering or a tighter directorial hand, the film has a way of lingering in your mind, like a sliver under the skin too small to grip but never letting you forget.

Is it great? No. But it’s better than good, if only because, in the end, it hurls a grenade at my expectations and for one wounded, weird, late moment, fails to let the story off the hook. I walked away rattled, a little stunned, and, not quite able to shake the image of Taraji P. Henson’s face, contorted by the kind of pain Hollywood so rarely lets women of her caliber, truly embody. That’s a minor cinematic miracle, and I’ll take those, clumsy, battered, and all, where I can find them.