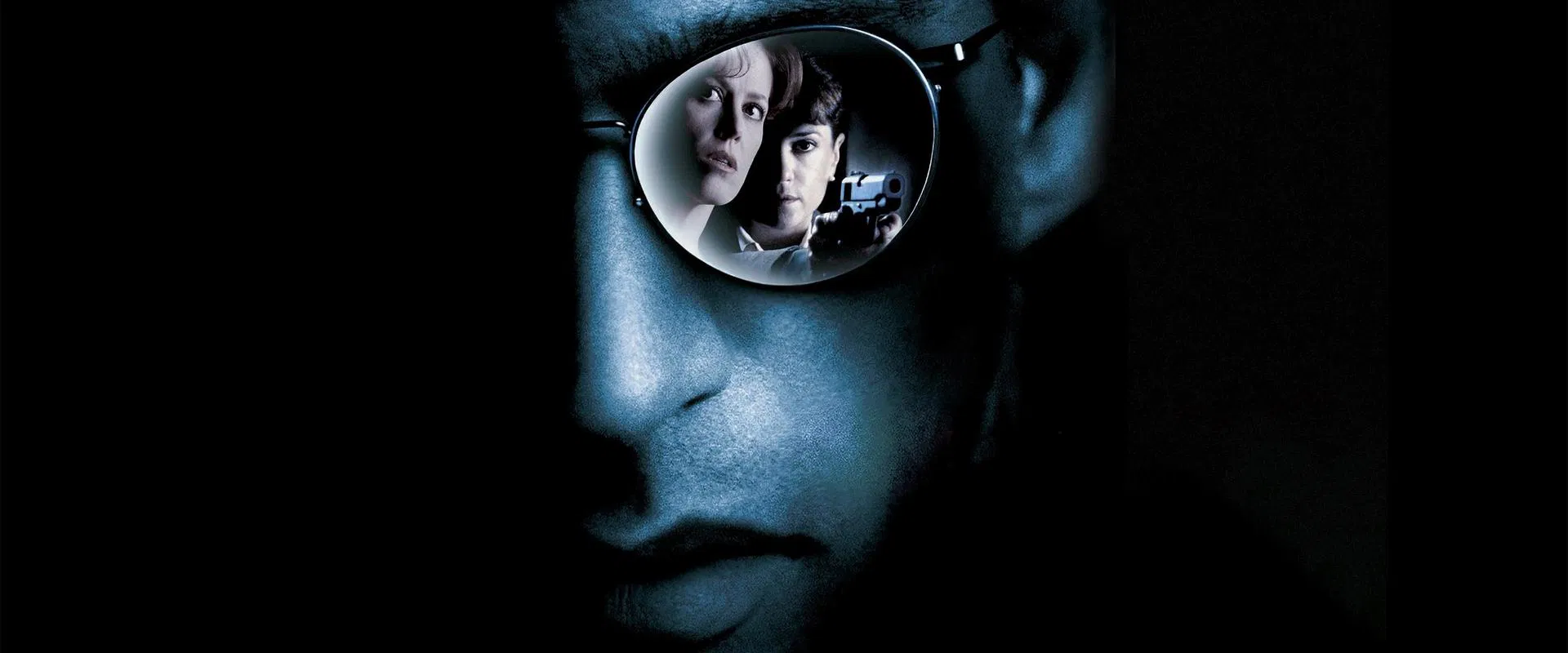

There’s a curious electricity that runs through Copycat, a film too calculating in its own self-regard to ever really slip the leash and become what you want it to be—a nervy thriller or a macabre descent or even a sly commentary on its own genre-mad duplicities. But isn’t that late-‘90s Hollywood for you? They always want to have a clever setup, the air of psychological sophistication, and Sigourney Weaver locked in a crystal palace of agoraphobic terror—yet heaven forbid they ever let too much chaos creep in. Copycat is the sort of movie that blows a kiss in the direction of Silence of the Lambs but recoils from Hannibal’s chill. The difference, of course, is that Jonathan Demme’s movie had an actual pulse beneath the politesse and a villain who seemed to spiral out of the cracked American psyche like a bad dream. Here, the nightmares all come from old clippings.

Jon Amiel (does anyone remember Jon Amiel?) directs with the anonymous, colorless precision of a reasonably well-credentialed television craftsman, so we’re denied anything like true visual style—nothing to make your skin crawl, nothing that makes the Bay Area feel less like a location in a chase scene and more like the haunted terrain of an American horror. The plot is clockwork, but one with jammed gears: a serial killer who “copies” the greats, with each successive murder a grotesque paperback pastiche—Dahmer here! Berkowitz next!—but instead of deepening into a meditation on evil, the film just keeps showing us newspaper headlines and inviting us to admire the research. You’ve seen this before, the movie seems pleased to say, but look: we’ve catalogued it.

And yet, the pleasure—the reason to see Copycat, and the only real reason to remember it—is the cold, flinty miracle of Sigourney Weaver. God, she’s good, isn’t she? There’s something about her that refuses to evaporate in a role, even when the script seems hellbent on making her into a Wikipedia entry with PTSD. That scene—yes, the one where she instructs the white men in her lecture hall to stand up, to gaze with self-satisfied discomfort at the fact that statistically, yes, they’re the menace—flashes with the only real subversive thrill the film allows itself. In another world, in another film, this would be the keynote of something more jagged, an indictment of the way our culture keeps manufacturing these predatory men, and the women who have to anticipate them.

Too bad the rest of the movie wants you to believe, in the hoariest blue-light fashion, in the unassailable world-saving heroism of the police. Somewhere in the writers’ room (you can smell the cigarettes and the bad coffee) someone must have said: “Sure, the cops in every other movie are idiots, but not ours. Ours will be saints. Competent, compassionate, cool under fire.” It’s propaganda, and a dull kind at that—the city as police procedural, played backwards and upside down so the audience never doubts who’ll show up in the final reel. Holly Hunter and Dermot Mulroney do their level best to give shape to the uniforms; Hunter in particular brings her jittery, birdlike energy to a part that otherwise reads like the weekly minutes of the homicide department’s Trust Building seminar.

The killer? Let’s not pretend there’s any mystery: he’s about as generic as the packaging on a shrink-wrapped crime novel left in a laundromat. William McNamara fidgets and glowers, but he can’t scare a cat, let alone the audience. The best moments—almost the only moments with any psychological crackle at all—come from Harry Connick Jr., who attacks his Hannibal-lite role with a galumphing, grinning carnality. You can see him playing at being Buffalo Bill, and it’s a little embarrassing for everyone. But at least it’s alive.

It would be too easy to dismiss Copycat as a product—and it is a product, straight off the studio assembly line, fed by the growing hunger of the home video market (didn’t you rent it? of course you did, everyone did, that one Saturday when you’d already seen Se7en twice). But the thing about middling movies—about movies that hit “good” with the practiced monotony of someone clocking in for a night shift—is they often end up being exactly what the audience wants: just clever enough, just suspenseful enough, just chilling enough, and just familiar enough to provide that comfortable, shrink-wrapped disturbance. You watch for Sigourney enjoying her own nerves, for Hunter’s choppy dialogue, and maybe for the eerie familiarity of it all: the pageantry of murder transformed into a kind of pop-cultural wallpaper.

Copycat is what you’d expect, which is sometimes exactly its problem. But within its suffocating genre bonds there are glimmers of something sharper: the gleeful provocation of that lecture, Weaver’s mounting, trembling resolve, and those moments—and only those moments—where you wish someone had strangled the script, let the actors loose, and allowed the movie to become the copykiller it so desperately wanted to be.