There’s a mordant joke running through “The Killer”—practically a pulse, arranged with the precision of a Smiths beat—that might be missed by anyone still taking their assassins straight and their directors at their own promotional word. Here is David Fincher, once the feverish chronicler of men unraveling in the glow of green computer screens and kitchen fluorescents, now orchestrating a liturgy of control and cold-blooded process so sharp it’s almost a parody of itself: the assassin as Ikea monk, building murder out of flat-packed routines and hide-in-plain-sight anonymity. Nothing, not even the violence, is ever allowed to descend into real chaos—not while there are yoga stretches to be done and a running tally of BPM on the Apple Watch.

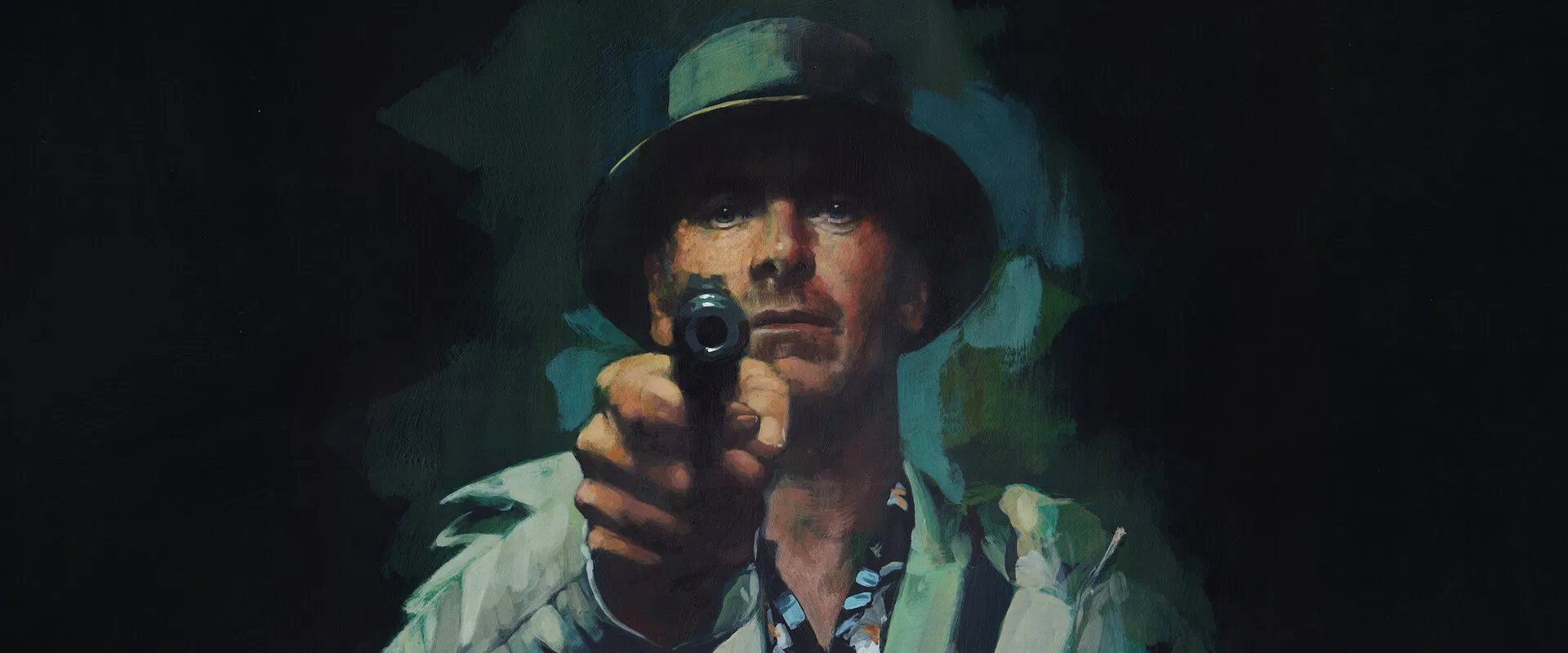

I admit, getting into “The Killer” required more discipline than the protagonist’s daily regimen—something about those first ten minutes, the antiseptic Parisian eyrie, the self-serious monologue, repelled me five separate times. Is there anyone left who isn’t a little allergic to groaning, noirish voiceovers? But Fincher—like his killer—rewards a certain persistence: around the time the world’s most meticulous hitman misses his shot (botching his job in a way that feels less narrative twist, more desperate self-awareness), the film wakes up and stretches its limbs and shows a sliver of something close to wit. Watching Fassbender prowl his WeWork lair, a Spotify playlist on and an espresso cooling at his elbow, you have to wonder if this is Fincher skewering the whole genre, or simply giving up the ghost of sincerity and laughing right along with us at the idea of the perfect assassin.

It may sound like overreading—or underappreciating the joys of a stylish thriller—to say this feels like self-portraiture, Fincher winding his own obsessive screws for the camera, but how else to explain the sheer pleasure with which the film lingers on process? Every cut, every angle, every ritual is so fastidiously plucked of mess that one wonders if Fincher is, at last, confessing to the charge made by his detractors all these years: that control is a kind of sickness. Or perhaps he’s just enjoying himself too much to care. The voiceover—so pretentious it’s almost parodic, the litany of rules constantly broken by their author—delivers all the pleasure of an old-school procedural, half Dashiell Hammett, half Marie Kondo.

What Fun: the Smiths, those arch-angels of melancholy, scoring the kill—a Fincher joke so perfectly on-the-nose you can almost imagine him grinning in the editing suite. There’s an acid humor here, cold-blooded but exhilarating, right down to the running meta-narrative of a man who expects perfection and is forced, by a world that refuses to cooperate, to improvise. You get the sense the real subject isn’t assassination, but artistry: what happens when the pursuit of the flawless runs headlong into stupid, unpredictable humanity.

That jagged, post-botch sequence—the futile attempts to control the damage, the brisk, almost bureaucratic disposal of accomplices and obstacles—brings out the best in Fincher. The standout scenes are icewater-cool and wincingly logical: the secretary Dolores, bargaining her way to a plausible death for the sake of her children’s insurance claim; the restaurant confrontation with Swinton’s “Expert,” which plays like an after-dinner mint composed of sandpaper and arsenic. Swinton, all faded Olympian grandeur, has a Brora single malt stashed for her final toast—one last luxury denied by the procedural bleakness of her fate, Fassbender draining the rare whiskey before putting a cheat’s end to her schemes. The note is perfectly Fincher: cold, unsentimental, more interested in the logic of endings than their emotional residue.

All of this would be sterile—a work of style as self-regarding as a mirror in an empty room—were it not for the film’s sly awareness of its own machinery. It’s not a case of no loose ends so much as the utter pleasure of seeing every last one clamped shut with professional indifference. The violence, when it comes, is quick, unceremonious, and never quite “fun”; there’s extraordinary tension, yes, but little catharsis. If you want Tarantino’s firework-ballets or De Palma’s swooning set-pieces, you’d best look elsewhere; Fincher directs with the appetite of a forensic accountant—every prop accounted for, every action checked off, the shooter and the director both disgusted by waste.

And yet, that chill in the gut—the voyeuristic pleasure of watching a craftsman, even one as odious as this faceless killer, do his work—is hard to shake. Fassbender is an actor made for surfaces; he’s always been cooler than his material, a man whose hunger for inspiration runs close to revulsion. Here, Fincher scours him down to something so anonymous it becomes universal: anybody can be a killer, the movie whispers, if you only have the patience for it. You wonder if Fincher, in the end, is making a case for his own work ethic: perfection is unattainable, and the best we can do with disappointment is tidy up after ourselves.

I’ll confess again: it took me more than one try to get past the cool, glassy façade, but once inside, I was hooked. “The Killer” isn’t just a technical exercise or nihilist’s funhouse; it’s a sneer and a wink, an autopsy of perfectionism, and perhaps the only satire you could make about someone who can’t allow himself to see the joke. Is David Fincher making fun of himself? Perhaps. But he’s also, it’s clear, still a devil at conjuring up those cold, necessary pleasures: the cogs turning, every loose end tied off, and not a drop of sentiment spilled on the Brora.