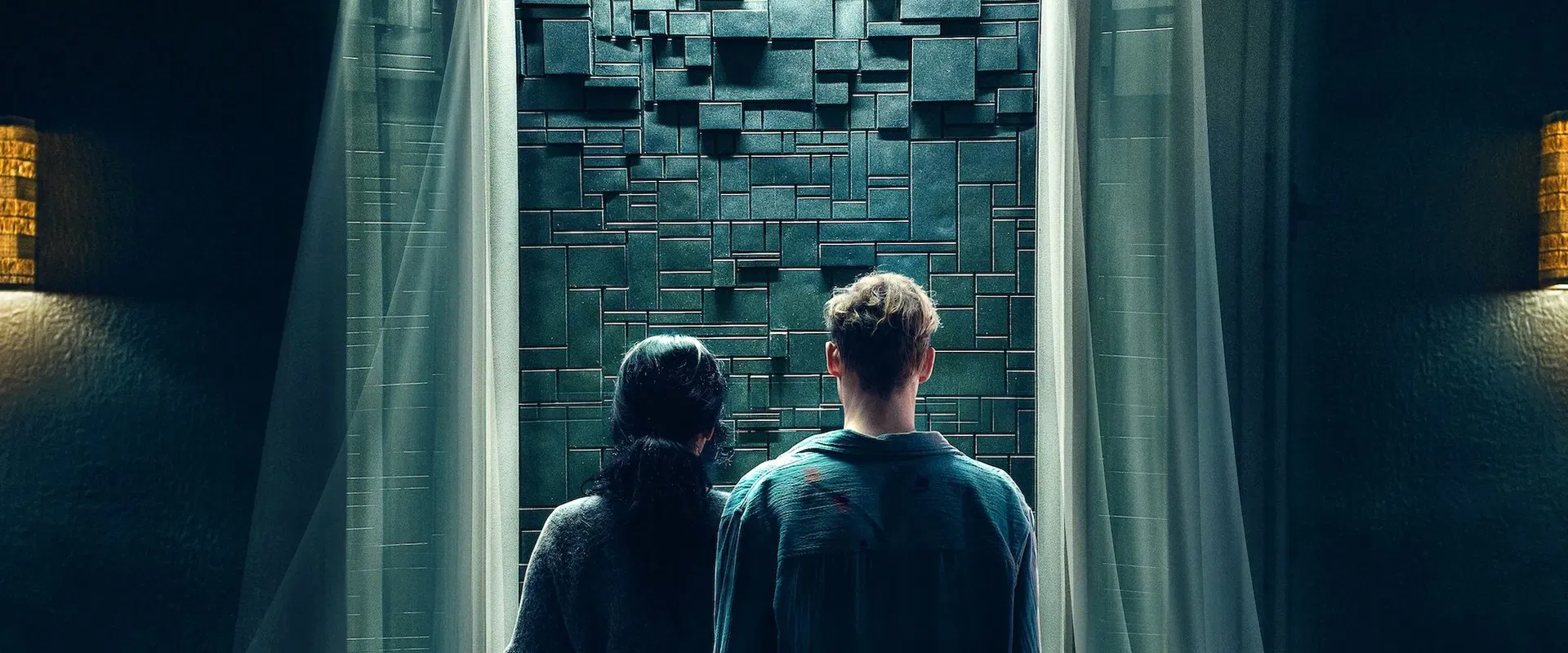

There’s something peculiarly demoralizing about watching a movie desperate to be clever—a kind of Netflix-age puzzle box that delivers nothing but more boxes, and each lid is glued on with the icy sweat of someone who thinks the riddle is its own reward. Philip Koch’s “Brick” (and has a contemporary German film ever worn a lamer Anglo title with such self-importance?) throws its benighted cast through every doomsday apartment-escape cliché you can think of, as if J.G. Ballard and J.J. Abrams had teamed up for a group project and then swapped out their last pages for a tech manual, all in the forgotten hope of stealing a march on “Black Mirror.” If there’s a greater argument for the superiority of television’s brisk forty minutes over the joyless slog of a two-hour feature, I haven’t seen it.

The premise—tenants in a Hamburg building suddenly walled in by a black, nanotech barricade following some unspecified cataclysm—could have been chilling in its Kafka-by-IKEA way. But “Brick” slaps on the chrome and gives you the sense that no one behind the camera has ever actually felt the horror of being trapped, only the nervous, artificial itch of people who watched “Cube” a decade ago and took the wrong notes. For every clever rupture, there are two new plot holes, shorn of sense but abounding in irony: Why does the landlord have a hidden lair stuffed with screens if all the feed’s silent, useless, and indiscriminate—artless voyeurism as the ultimate non-act? Why is everyone being watched, and by whom, for what? Don’t ask. The only thing “Brick” will reward is your patience, and that, I warn you, is in distressingly short supply.

There is a moment—one of the faint embers of logic left to us—when Olivia, game (and gamey) architect played by Ruby O. Fee, makes tea for her almost-ex Tim after the water should absolutely be gone. Never mind; perhaps it’s supernatural tea, or else this is simply the logic of contemporary screenwriting, where the hands reach for props because the script needs a gesture, not because sense needs serving. So it goes throughout: characters perform tasks because someone, in a writers’ room or peculiarly German committee, decreed that something must be done.

As for the band of captives—and here is a parade of names as if every Spotify account in Germany had voted for who should live and die—there’s all the usual teamwork and betrayal and death and self-pity, but precious little actual character. Only Frederick Lau, as Marvin, seems to have understood that a person under siege in a sci-fi horror is allowed not merely to whine, but to rage, to panic, to outmaneuver death with more than a tired quip or a pained squint. The rest—Matthias Schweighöfer, who I used to enjoy as the rubbery, madcap heart of “Army of Thieves,” is here reduced to a man whose contributions could be replaced by a looping .gif of bafflement. It’s a thankless role, in a thankless film, and he flounders like a man who arrived on set expecting to rob a casino and was instead handed a plastic sledgehammer and a script full of holes.

And, dear God, the holes. I begin to suspect that the titular “Brick” refers not to a building material, but to the density of the plotting. How did any of this happen? Why does the landlord have his hands chopped off—is this the movie’s feeble nod to irony, cruelty, or just convenience, like some dimly-lit “Saw” motif glued on as punishment for attempted narrative? If he lost them to his own trap, does that mean he was a brilliant recreator of another’s code, or just another pawn in the movie’s assembly line of “mysteries” destined to evaporate the instant you question them? How, for example, does Yuri survive being shot, only to rise again for a final round of chaos—a Lazarus with the purpose of a broken drum: to make noise, not music? None of the deaths here land as more than functional obligations; Ana’s sticky-fingered dematerialization into the magic wall, performed with all the suicidal curiosity of a child prodding at a wet socket, is less gruesome than it is monumentally stupid.

There is, embedded somewhere deep within this Rube Goldberg mechanism swaddled in Euro-budget gloom, the prick of a genuinely clever idea: a trap, an experiment, a puzzle-box house with codes to crack and alliances to break—fine, fine, so far. But Koch and his collaborators never realize that tension is built not by piling up clues, but by letting us care about the sweat on characters’ brows; instead, each new “twist” comes off like the most recent update on a phone app you neither wanted nor needed. And their fatal error is believing all this is clever enough to sustain itself for hours—when really, a 30-minute “Black Mirror”–style episode could have delivered every one of their ideas, and spared us the endless double-backs and exposition. (I imagine the English-dub is the final insult; at points, it’s as if the actors are auditioning to voice assistant apps, not real people.)

The ending lands with a flat, joyless thud. The surviving couple tumbles into the daylight after vanquishing, by process of deduction and by the luck of elevator music, the Final Boss of Inconsistency (Yuri, again). The curtain lifts to reveal—not answers, not emotional catharsis, but a city anesthetized by another “big twist,” leaving you only to wonder: what was it all for? Narrative is insulted, logic assassinated, and the audience, I fear, left shaking in numb confusion.

There is a certain pleasure in genre movies that don’t take themselves seriously, but “Brick” is convinced it’s constructing a masterwork and produces only a set of taunting riddles, with a human cost measured purely in patience. Skip it, unless you’re desperate to see a talented cast scramble about in a maze that never unlocks its own secrets. You’ll find yourself—like the tenants—in search of a way out long before the credits roll.