Let’s strip away the illusion: Land of Bad is the cinematic equivalent of a greasy cheeseburger at midnight—no one will claim it’s haute cuisine, but good lord, sometimes you just need it. It’s the type of picture that wears its lack of originality like dog tags, draped proudly over a flak vest of tropes. Oscars? Not unless they start giving out awards for Most Satisfying Detonation or Best Use of a Helicopter in a Crisis. But when you’re hungry for sensory overload—explosions, cussed camaraderie, men shouting “Go! Go! Go!” into static—who’s keeping score?

This movie is honest about its purpose: it’s a pump of pure testosterone, a buffet where every dish is some variation of kaboom or not-on-my-watch grit. No shame, no apologies. If you’re here, you want to gorge on action, and Land of Bad sure gives you second helpings.

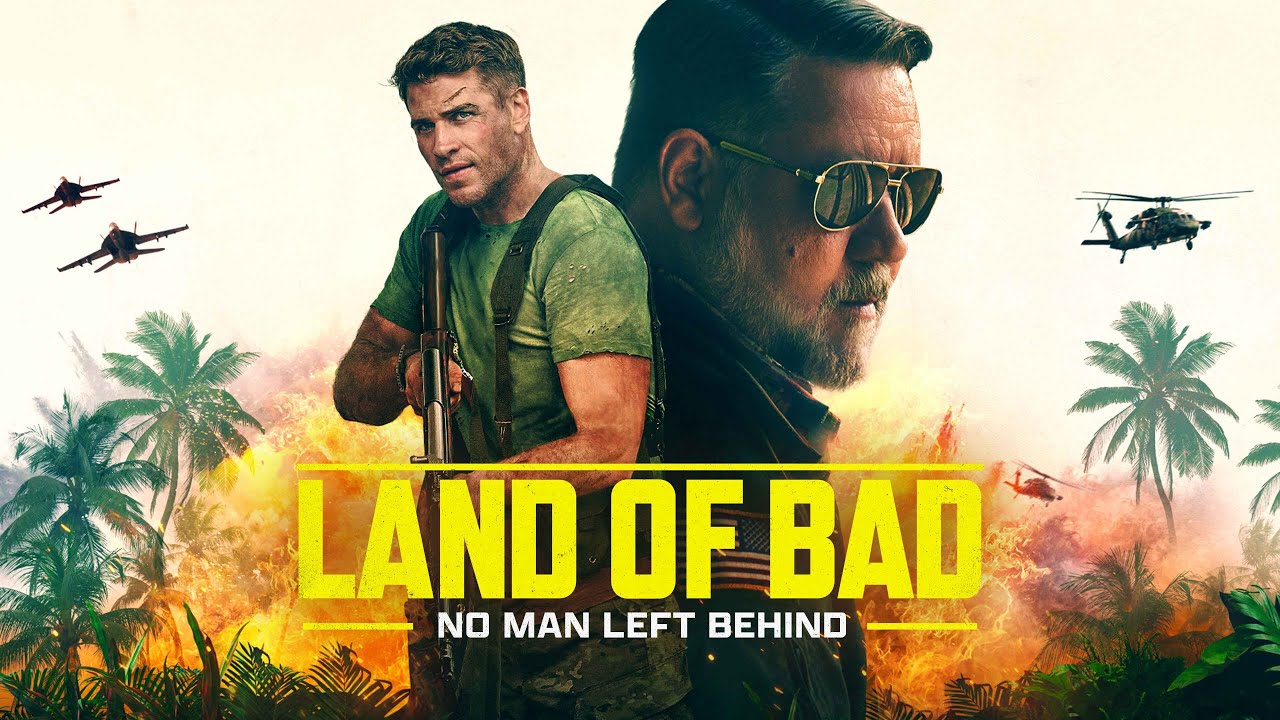

The setup is as old as the hills—no, older, as old as blockbusters themselves: Liam Hemsworth, all earnestness and baby-blue ambition, is the new recruit shipped out for his big-league mission. He fumbles toward heroism with that faint, wistful ideology only a true action movie rookie can muster. Enter—crashing like a fridge through patio glass—Russell Crowe, the gravel-voiced drone pilot eyeing the chaos from afar but never too far to keep his hands clean. Crowe’s drone jockey doesn’t just chew the scenery; he gives it a nicotine patch and a death glare. You know from the first curl of his lip that this man’s watched more men die on monitors than you’ve watched reruns of Die Hard. When Crowe and Hemsworth share the screen, it’s a collision of generations: one pure, anxious pulse, the other petrified into a callus. Their banter has a pulse, too—a jerky rhythm between revelation and resignation.

Plot? Of course there’s a plot, in the way you know there’s going to be bread at the diner. Our duo stumbles (sometimes literally) into a rescue mission in the Philippines that falls apart with clockwork efficiency. The “oh, it can’t possibly get worse” principle is observed scrupulously—each firefight only serves to prove that, yes, it actually can. Director Will Eubank is no Altman—he has no interest in subtlety or tangent; he just spits you straight into peril, resets the timer on the next crisis, and keeps the pedal jammed somewhere between “imminent threat” and “total wipeout.” The result is a kind of relentless cinematic CPR.

But let’s linger, for a split-second, on Crowe. He could easily have phoned this one in—barked a few orders, stared wistfully at a dot on a screen, and picked up his paycheck. Instead, he brings a worn-in authority, a kind of gruff fatalism that makes even the most leaden lines (“We’re outnumbered and outgunned”—as if there were any other sort of gunfight worth watching) sound almost like wisdom. You keep watching Crowe’s eyes for a glint of lost idealism, but see only the cold reflection of a thousand washed-out screens—and that, somehow, gives the movie ballast.

Hemsworth, meanwhile, plays the rookie as if he’s aware the genre won’t let him stay innocent for long. There’s something almost sweet about his confusion turning to resolve, his face registering—again and again—that blend of Are-You-Kidding and I-Guess-I’ll-Do-It. He goes from wide-eyed adrenaline-puppy to blood-streaked, mud-caked survivor with admirable efficiency, and if it’s not a transformation for the ages, it gives the movie just enough of an arc to hang your thrills on.

But let’s not pretend action is garnish. Action is the main course, the dessert, and the espresso all in one. Eubank comes armed with his list—explosions, check; ambushes, check; jump from helicopter, double-check—and ticks every box like a kid set loose in the fireworks aisle. If it sometimes feels mechanical, there’s still an unvarnished pleasure in the grit and sweat of these sequences. At one point, the chaos achieves a kind of kinetic purity; you actually feel your own blood pressure rise.

There’s something almost refreshing about the movie’s refusal to be anything but what it is—a straight, low-fat, high-calorie adventure, uninterested in adding a garnish of subtext or injecting a metaphor where a shotgun blast will do. The cinematography matches this mood: handheld, blunt, kinetic, smoke and sun-blast and shrapnel colliding in your eyes. The soundtrack hammers the point home—no, you aren’t allowed to relax.

Land of Bad is, in the end, a guilty pleasure that’s unashamed of its own diet of cliches. When you want a salad, go watch Bergman. When you want meat—preferably raw, and flung at your face—this is the meal. It doesn’t reinvent the genre, it doesn’t even want to. In a cinematic world of failed ambitions and delusions of grandeur, sometimes the only honest move left is to blow the roof off, reload, and watch the wreckage with a half-crazed grin. For action buffs, this is comfort food with live ammunition.