Every now and then, Hollywood hatches a marketing campaign so clever it's almost tempting to review the movie poster and be done with it. “Longlegs,” the latest generation of viral internet bogeyman, slithered into theaters on a fog of clickbait. It arrived, stuffed to the gills with promises—a “new Silence of the Lambs,” “the scariest movie of the century!”—as if mere dread could be manufactured wholesale, like bootleg perfume. I kept waiting for the stench of brimstone to hit me in the nose, but mostly all I caught was the distinct aroma of overbaked expectation.

Osgood Perkins, who has clearly been slipstreaming David Lynch’s nightmares and burrowing through his own father issues, gives us a vision of Satanic evil loose in suburbia—a purgatory where family rooms breed more ghosts than comfort. Much like “Se7en” in its funereal detachment, “Longlegs” isn’t content to set its story in the world as we know it: the movie is staged in a kind of hollow chamber, where voices don’t quite ricochet but echo mutely into the void. The only things that feel truly alive are the nervous camera and the sound design, both working overtime to convince us something unspeakable is worming its way through the floorboards. If you want deja vu, you’ll find it within the very fibers of the movie: Lynchian Americana, Zodiac diagrams, and B-movie Satanic Panic—all folded together with just enough sincerity to look like a Frankenstein’s monster summoned from IMDb’s “People also searched for.”

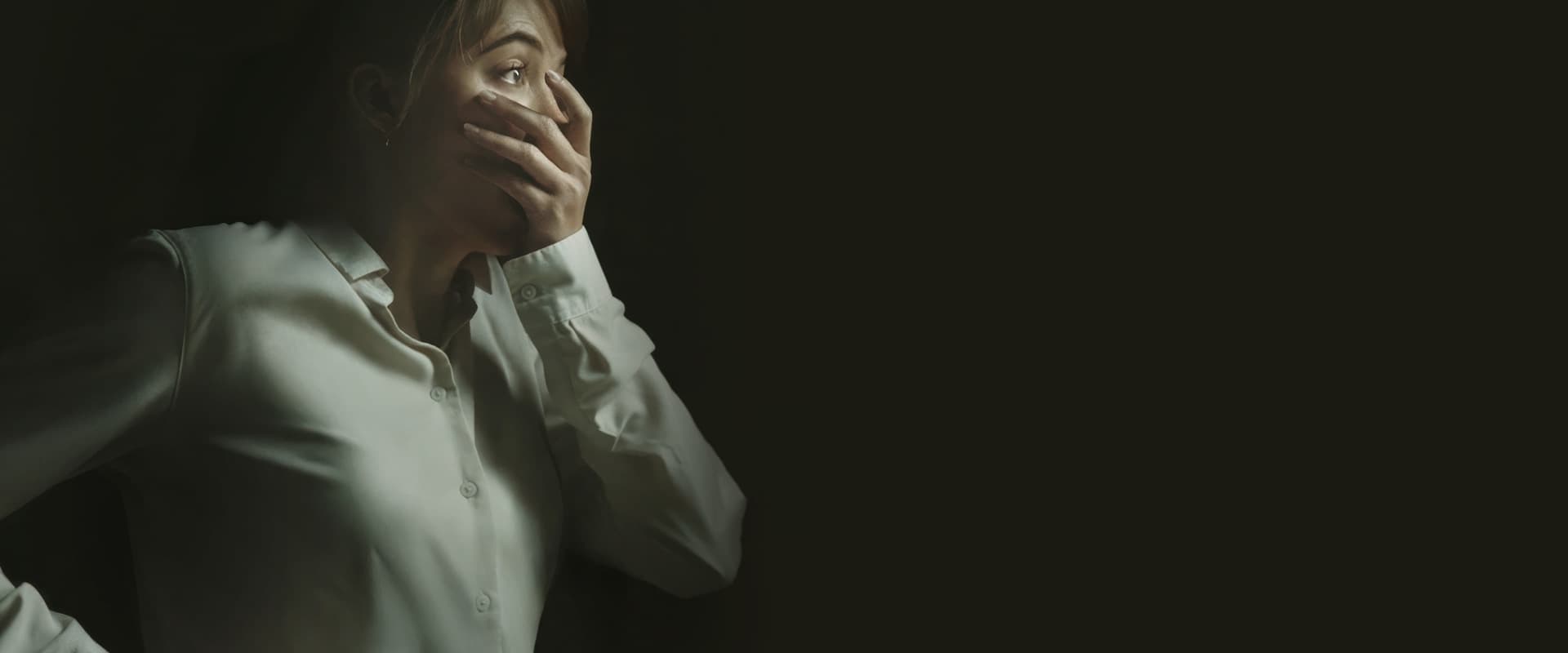

It’s impossible not to feel a spark at the start. For a reel or two Perkins is having himself a little séance, conjuring up atmosphere and a couple of honest-to-god goosebumps. The mood is deliciously off-kilter—the jokes hit at just the wrong angle, the weirdness is inviting rather than obnoxious, and Maika Monroe’s steadfast, shell-shocked agent pulls us into the puzzle with her unsteady composure. Monroe is so good, so fundamentally real amid the twitched-up supernatural hokum, you start wondering if the entire genre isn’t quietly conspiring to underutilize her.

But dread is a solvent, not a destination. You can only hold people in suspense for so long before the story has to get on with it. Like the magician who can’t resist explaining the prestige, Perkins’ script turns explicit—his trick is showing the wiring inside the corpse. Every wisp of strange rarely has a chance to rot before it’s pinned to the plot and explained within an inch of its life. By the time we’re mounting up for the climax—a smorgasbord of procedural tropes and illogic—the movie seems determined to both unravel and contradict itself. It’s as if someone, somewhere, started worrying that things weren’t making enough sense, and reedited in a flurry, treating the audience like we’d left our brains in the car along with our crucifixes.

Nicolas Cage, who appears on all the posters as the devil you know, is wheeled out for a handful of scenes, jaw slack and eyes rolling heavenward—his particular strain of overripe Cage-ness as comforting as oatmeal gone tepid. The makeup, an unholy cocktail of Marilyn Manson and a third-tier John Waters extra, generates exactly zero unease. All that’s left is a peacock display of fussy malevolence, every cackle and croak squashed under the weight of how much we’re supposed to be freaked out. Truth is, the less you see of him, the more enticing the mystery; an ounce of restraint goes a long way in a movie that otherwise can’t stop talking.

Perkins’s best movie, “The Blackcoat’s Daughter,” was a near-mute little horror poem—here, his recurring obsessions with familial trauma, broken daughters, and the possibility of evil run rampant aren’t deepened but underlined in fluorescent marker and then recited aloud (“the doll symbolizes repressed memory,” someone might as well announce). The supernatural is at war with the procedural, and neither wins: what’s left is a kind of awkward custody dispute where style gets the kid every second weekend.

The parade of genre influences—pagan triangles, demonic dolls, suburban dread—has the flavor of a greatest-hits compilation. I kept wishing for a new track. There’s a moment where Maika Monroe holds the center so tightly you think: this could become something special. But the narrative is content to drop motifs like cursed breadcrumbs, leading to nowhere but another paved-over set piece, another mystery solved not by horror but by plot convenience.

If you want to know what “Longlegs” is, strip away the advertising: it’s a nicely-dressed B-movie with a digital sheen, a halfway shocker caught between art and algorithm. It wants to scare you witless, but has the slightly desperate air of someone telling their own ghost story and not believing it themselves. You’ll leave the theater perhaps buzzing, but mostly because the communal hysteria tells you you’re supposed to.

Is it the next “Silence of the Lambs”? Not in the same time zone. “Se7en”? It wouldn’t survive the first round with Fincher’s hellbound detectives. The comparison is a nervous tic, a symptom of the genre’s insecurity—a hope that, if we say it enough, this time it’ll stick.

But I can’t make myself dislike “Longlegs.” Perkins is a craftsman, he has taste, and there’s a certain modernity in his willingness to try something stranger, broader, less satisfied with the old rules of spooky cinema. I just wish my heart rate had gone up for more than a scene or two. I wish the resolution weren’t so stilted, so overeager to explain itself. Most of all, I wish the movie’s devil didn’t feel so small—nowhere near monstrous enough to haunt the infernal hype that birthed him.

Not the scariest of the year (not even close), not the masterpiece that the internet is hungry for, but a refreshingly ambitious failure from a director who’s still sculpting his own cinematic weirdness. Go, if you want to see how the sausage is made. Just don’t expect to taste blood.