There is, let’s be honest, a certain adolescent joy in being bad for the sheer, unlaundered thrill of it—a kind of cackling, slippery impudence most modern horror movies outgrow in favor of handwringing, pious detours into “trauma,” and a double-locked justification for every sharp object. Watching Terrifier is like giving a chainsaw to the class clown and seeing how many teachers he can send packing: it doesn’t care about lessons, or roots, or the sob story behind the mask. It’s a daft, dangerous revel stripping horror down to the giggle you stifle when you know you shouldn’t laugh, but can’t help yourself.

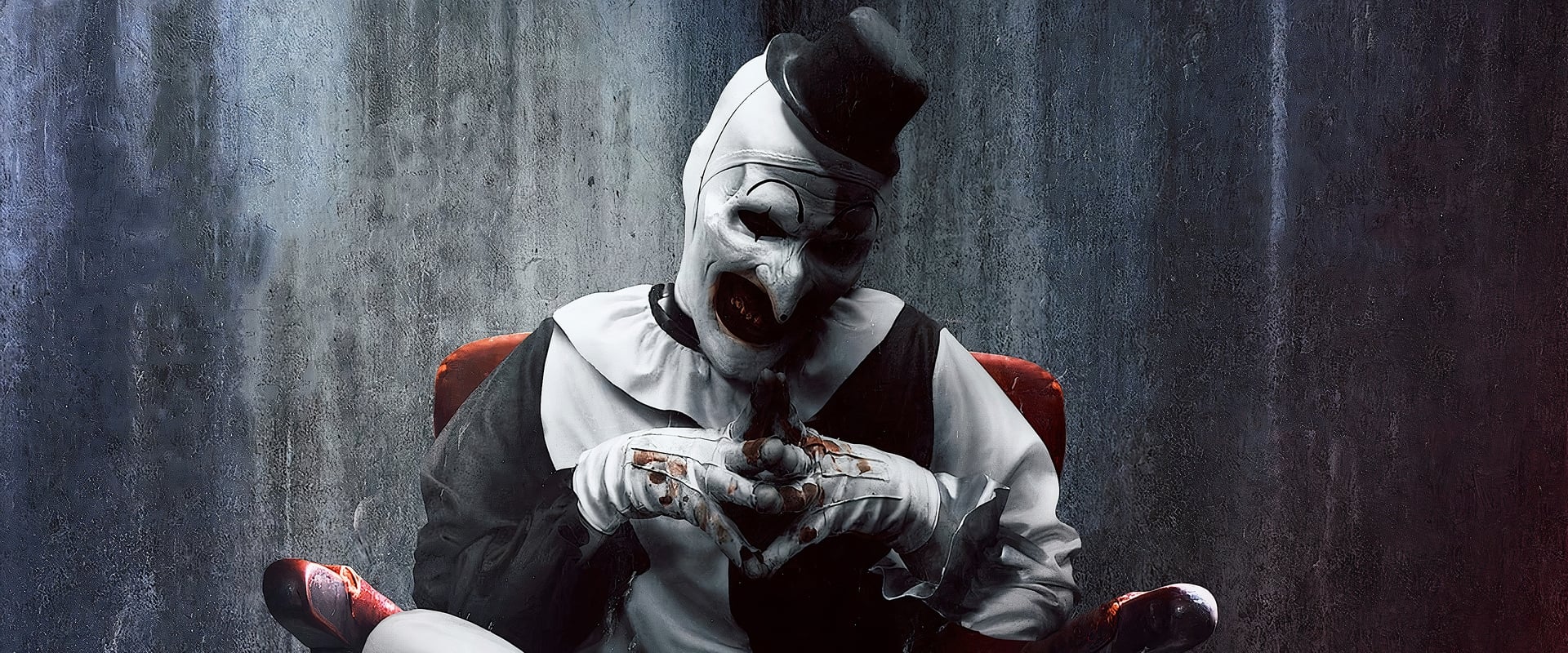

Almost everything in horror now wants to be the lecture at the end of a juvenile delinquent reel: see kids, the monster only rampages because his mommy didn’t hug him and society failed, may we now have our A24 merit badge? Meanwhile, Damien Leone’s only public service is to lock you in his midnight spookhouse and throw away the key. Terrifier swaggers onto the screen with the dead-eyed, greasepainted grin of Art the Clown—a villain who doesn’t inherit from his masked predecessors, but mugs for your attention, boots out any lingering whiff of “meaning,” and turns carnage into the rowdiest midnight vaudeville in town. No backstory, no tragic exegesis, not even the pretense of a “code.” Art’s the black hole at the end of the horror video aisle, the zany afterimage burned onto your eyelids after too many bad dreams in a row. He’s the mall Santa who bites.

And of course, it’s Halloween—America’s annual permission slip to tiptoe past the graveyard, gorge on sugar, let the children flirt with oblivion under the porch light, while the movies slip their leash and bare their teeth. Carpenter gave us the mute suburban shadow; Leone offers us his monkey’s paw cousin, pulling faces, hamming for our cellphones, making a howling joke of the whole slasher tradition. If the last decade has been all about homage and pastiche—the careful quotation marks around every scare—Leone couldn’t care less. He’s running a sideshow, jettisoning story, dumping exposition like dead weight. Here, structure means an anatomy chart. Why is for people who still lock their doors—Terrifier is all about how far, not why, and it keeps going until you’re fumbling for your safety word.

David Howard Thornton’s Art, and let’s be clear, is simply what happens after the rest of the horror monsters have been gnawed clean of subtext: leftover performance as skin-crawling standup, each pantomime a little love letter to anyone who’s ever smirked their way through a body count. Thornton doesn’t act—he infects the movie, working his way into your nerves with mime-comic business, sidelong glances, slapstick that goes to pieces and never gets put back together. Art doesn’t need a voice—his silence drills a hole in your comfort. He’s Harpo Marx after a head wound, all jest and arterial spray, making you laugh right up to the moment you realize you’ve crossed over to hysteria.

And antics—yes, it’s the right word; Leone’s setpieces make you wonder just how loud he laughed writing them. There’s one, involving a hacksaw and a splayed grin at the fourth wall, that earns its place in the icky annals of horror history because, for a couple of minutes, your own response toggles crazily between amusement and open-mouthed recoil. Thornton makes you feel seen, and not in the therapeutic sense; he seems to register your squirming in the dark and escalate on cue. If there’s ever been a monster who murders with a punchline, Art is him—a joke that drags on until the tap is running red.

Characters? You want characters? Jenna Kanell’s Tara is handed the usual “Final Girl” survival kit, then snatched offstage before she can even brandish her last wisecrack. Samantha Scaffidi’s Victoria endures, or something that passes for it, but you don’t get twists of personality here, only the sense of someone left standing at the end of an earthquake. The rest? They’re the demolition derby crowd—cannon fodder in the world’s gaudiest Halloween parade. If you want acting, rent a costume drama. What you paid for is carnage—and so did Leone.

But let’s not pretend: there’s an honesty—a rude, slapstick purity—to the way Terrifier treats us. If your idea of valid horror is a CGI spitball, this movie is a bucket of cold water and pig guts, deliriously old-fashioned in its effects and mischievously delighted by its own excess. No computer trickery here—the blood hits the floor with the thud and spatter you remember, if you were ever perverse enough to like your horror wet and practical. The line between applause and retch is so thin Leone could thread a needle with it. For those who have felt cheated by “elevated” horror and its sermons, here’s the sledgehammer you thought had gone out of use.

To call Terrifier a throwback would be to miss the sulfurous glee that runs through it—it isn’t nostalgic, it’s lawless. Leone isn’t playing scholar or ombudsman for the genre; he’s mooning the faculty and triple-dog-daring you not to flinch. No catharsis here, no buried trauma: just the raw nerve, the exposed wire, chasing you up the aisle. It’s not about symbol, it’s not about meaning. It’s the cackle you can’t get out of your head, three days later.

So what is left? An SNL audition for sociopaths? A Halloween revue with knives? Maybe—though to me it feels like the closest thing to the primal, unruly riot that horror used to be, before the genre went soft and started sniffing after awards. If you get through Terrifier unmoved, you’ve either grown up too much or not at all. Art leers at you from the darkness, asking nothing, signifying nothing—a vacancy with a painted grin.

And if you stumble out the theater half giggling, half embarrassed, blinking in the lobby lights? Good. That’s what horror started as, before the critics got their hands all over it—a transgressive, ticklish, unholy rush that leaves a bruise just under your skin. Art the Clown, may your painted leer outlast us all.