Criminal is the kind of mongrel thriller that seems almost tailor-made to attract critical enmity: jigsaw plotting, characters that come apart if you prod them, and a magpie casting philosophy that shuffles through A-listers as if Hollywood were a novelty gumball machine. The reviews online drip with the sourness of dashed hopes—critics, wringing their hands about “wasted potential,” all but begging the film to be thrown back into the genre stockpot for more seasoning. And yet, perversely, that’s the exact pitch that drew me in. Give me talent forced to dance on rickety scaffolding over mediocrity any day; how else would we ever be surprised?

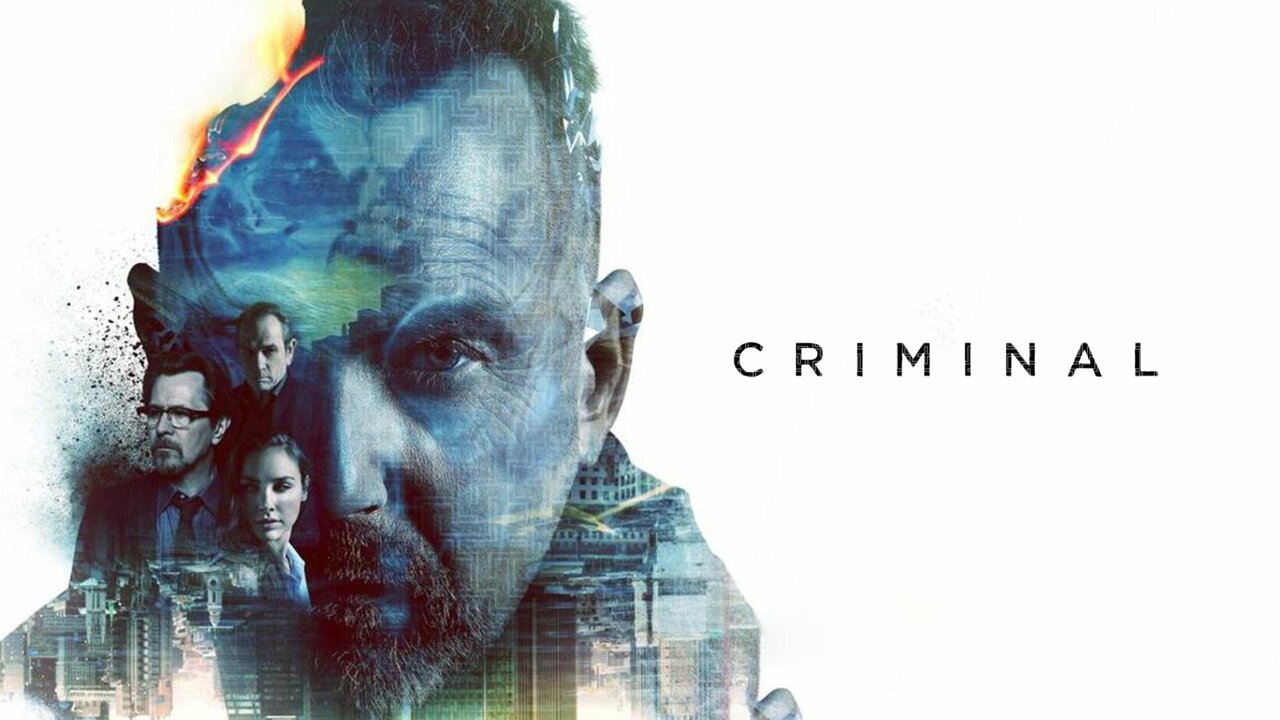

The real bait, of course, was the roster: Ryan Reynolds, Gary Oldman, Gal Gadot, Scott Adkins, and Kevin Costner turning up like strange cousins at a family reunion. There’s always a strange, kinetic hope that as the script tumbles along, some peculiar alchemy will ignite—a glance, a stray gesture, or a break in the formula that turns pulp into gold, if only for a heartbeat. (If you can resist the call to see all your favorites trapped together in this madhouse, you probably were never a real movie lover to begin with.)

Ryan Reynolds is, hilariously, the mainspring and also the first thing the film lets go of. His Bill Pope is dispatched so expediently it’s almost poetic—he’s the emotional fuse that sets the contraption ticking, his absence clanging around like a ghost in every subsequent scene. In those scant minutes, Reynolds delivers the kind of emotional shorthand that’s usually reserved for a “for your consideration” reel: alert, vulnerable, entirely present. It’s a performance that, ironically, haunts Criminal with something like heart—the real soul that Kevin Costner’s chimera, Jerico Stewart, will spend the rest of the movie clawing after in fits and shudders.

About Costner—this is the performance that causes a double-take: what’s America’s most stoic cornfield heartthrob, now firmly in grandpa-years, doing bulldozing his way through a role that demands both carnage and confusion? Miraculously—or perhaps just improbably—Costner sidesteps parody. His Jerico is a knotted ball of violence and bewildered yearning, a man reduced to his animal instincts suddenly infected by flickers of memory that bring yearning, remorse, and even flashes of love. It stings, in a sideways way: in the glint of pain behind Costner’s eyes, you sense what it might mean to have somebody else’s tenderness forced on you like a disease. The performance—uneven, occasionally overcooked—somehow works, precisely because you never stop questioning whether it should.

But let’s be honest, somewhere between shootouts, I caught myself running a better version of the film in my mind. What if Scott Adkins—whose very knuckles seem to have their own tragic backstories—had run wild as Jerico? Adkins brings a feral logic and physical truth to his roles; in Avengement, he turns violence into a kind of balletic confession. Imagine him pushed into the lead, bringing fatal brute conviction and wounded animal cunning. Criminal seems almost to tease with that possibility, letting Adkins circle the action but never quite giving him the keys to the cage. It’s a missed opportunity that aches all the louder once you picture the movie’s bones realigned by a bolder hand.

Yet for all the mania and turmoil, there’s an unlikely grace in the film’s quieter moments. The scenes between Costner and Gadot—herself radiant with hush, refusing to be reduced to mere window dressing—hover on the edge of profundity. These are the passages where Jerico’s internal struggle becomes almost noble: a bruised outsider stumbling toward love, redemption playing hide-and-seek within him. Gadot gives him—gives us—something to ache for. As she cradles the man who is and is not her husband, the violence evaporates and a stillness sets in, more breathtaking than a dozen car chases.

Beneath the bullet casings and body swaps, Criminal is preoccupied with who we are, what memories lurk beneath our habits, and whether redemption is a story only the sentimental still believe in. As Jerico unspools, haunted by another man’s griefs, the film edges—timidly, but sincerely—toward the existential. We inherit more than our genes: sometimes other people’s regrets nest in our skulls and their loves twitch in our hands. Criminal wants to be about that—the possibility that even the worst of us might be rewired toward decency by the force of memory or affection.

Of course, the film, true to its commercial DNA, isn’t content to stare at its navel for too long before reaching for the detonator. The action comes crashing back in—fists, bullets, gut punches, the works. In a world oversaturated by empty pyrotechnics, Criminal is at its best when the violence is just a surround sound to the flickering inner struggle, not the headline act.

And because Hollywood still knows how to thread a heartstring, you get “Drift and Fall Again”—sung by Lola Marsh, aching just enough to make you believe the movie might have earned its feeling. It’s the finishing glaze, the thing that lingers after the credits: a taste of melancholy that feels more hard-won than the rest.

In the end, Criminal is a film full of ghosts: of a better casting decision, of a deeper script, and most of all, of the lives and loves that trail after us—a Frankenstein patched from genre parts and sudden grace notes. It’s easy to call it a missed opportunity (God knows, it is), but those, too, can leave a mark. For a night, at least, I was content to be haunted by its beautiful, boneheaded ambition.