Steve Buscemi’s Animal Factory wants very badly to be that scalding, claustrophobic plunge into America’s penal underbelly—shadows slithering across dank concrete, sorrow corroding the air, all the usual tropes rattling their chains. But what you actually get is a drab shuffle through the same old cellblock, a movie so enamored of its own grimy surfaces that it forgets to find something compelling lurking beneath. It postures as neo-noir, but it might be the most ordinary thing ever dragged through a barred window.

There’s a reason some of us have a soft spot for prison movies: the formula’s simple, and when done right, it’s dynamite—compressed lives, intrigue, survival distilled down to glances and whispered alliances. But Animal Factory somehow mistakes “familiar” for “foundational.” I watched, waiting for that shiver of dread or brief, bitter camaraderie that makes a prison film pop—waiting for anything, really. By the time the “really, that’s it?” ending clanked shut, I felt like I’d spent a week in solitary, mulling over why I even checked in.

You know the drill: a baby-faced naïf (Edward Furlong’s Shaun/Ron Decker—does it matter?) stumbles into the yard with a look that’s half “don’t drop the soap” and half “my agent said this would stretch me.” He’s tossed to the wolves for a drug offense, and before you can say “institutionalized trauma,” he’s a tasty snack for every predatory cliché. In swoops Willem Dafoe’s Earl—a mentor whose brand of kindness clangs as obviously as the gates. There’s the requisite attempted assault, the close call, favors traded over thin soup. The plot skids on these rails with a doggedness I can only describe as apologetic. It’s as if nobody involved could summon the energy to do more than reheat yesterday’s news.

There’s a noble attempt to dress it up as hard-knocks allegory—prison-industrial complex, masculinity, the whole fatted calf. But these are just paint-by-numbers themes, fingerpainted and left to dry on that eternal cinderblock wall.

And what of the actors—the movie’s heartbeat, or lack thereof? Furlong churns up a passable soup of fear and confusion, but he’s left poking around in a script that treats vulnerability like a line-reading exercise. You almost hear the director off-camera: “Look scared, kid. No, really scared. Even more—like ‘I know this script is bad’ scared.”

Dafoe, God bless him, rages against the dying of the light, but he’s boxed in by a relationship so underbaked it could cure salmonella. Their scenes sway between stilted posturing and the awkward pauses of two men who can’t decide if they’re reading lines or waiting for a train. You wish them luck and pray the movie moves on.

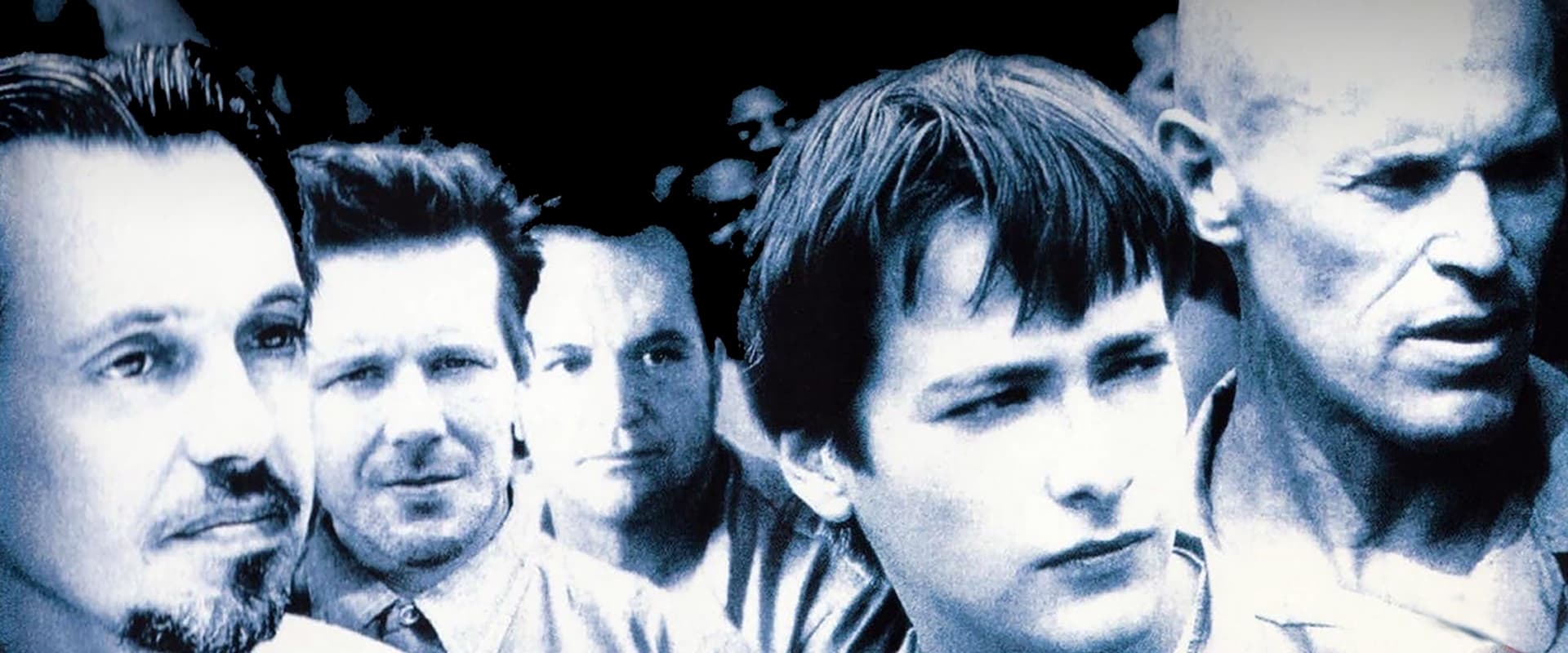

The supporting cast reads like a Hollywood “tough guy” roll-call—Danny Trejo glowers in a cameo built for the IMDb keywords, while Mickey Rourke, John Heard, Tom Arnold drift in and out like ghosts tasked with reminding you that, yes, famous people agreed to this. Nobody’s allowed the dignity of a fully realized human being; they’re little more than chess pieces in a game the script can’t be bothered to play.

For all Buscemi’s indie cachet, his direction here meanders like a prisoner lost in his own rec yard. He gestures at discomfort—the requisite bleakness and sledgehammer “authenticity”—but rarely touches anything raw or real. The movie wants to brandish its truth: “Look at all this suffering!” But the effect is closer to a grainy slideshow of prison cliché, with no vital pulse underneath.

Pacing lurches from manufactured tension to stretches of sedated dialogue, as if nobody’s sure whether this should be a thriller, a tragedy, or a lesson in nap-taking. It’s a visual flatline: the much-pitched “gritty realism” devolves into a series of dim corners, all so “authentic” they slide right off your eyeballs.

Let’s pause for the dialogue—or as I like to think of it, the Constipation of Screenwriting. Every now and then, a line gropes for profundity and comes up with the dramatic tension of a public service announcement. The rest is as pithy and recycled as slogans at a warden’s conference. If you played the “How Many Prison Movie Tropes Can You Hear?” drinking game, you’d be flat on your back before the second act.

Sound and score slink along in determined mediocrity; it’s a parade of echo and muted threat, as if the movie knows it’s supposed to sound important but can’t decide what importance actually means. Call it the Muzak of despair.

Animal Factory wants you to snack on big themes—survival, corruption, hierarchy, masculinity—but serves them up with such offhand lumpishness that you wonder if anyone involved cared about more than convincing Sundance they could be “raw.” Some of the most interesting possibilities—a mentorship verging on codependence, the way the prison grinds down even its “kings”—skim through the script like visiting relatives who don’t stay for dinner.

And then there’s the ending—less catharsis or grim twist than a whimper on a chalkboard. “Are you fucking serious?” Yes, I was, and I wanted my time back. There’s no payoff, no earned emotion, only the gnawing sense that the filmmakers rushed the escape just as their own creativity hit deadlock.

If Animal Factory teaches us anything, it’s that you can tick every box for a “serious prison drama” and still land in movie purgatory. It’s not a disaster, just a slow, self-conscious shrug. A drab, wish-I-hadn’t-bothered tour—like the worst kind of prison sentence, where the only thing you remember is how numb you felt.

Prison movies, at their best, prison-break you into humanity’s messiest corners—but this one forgot to smuggle in a soul. If you’re a devotee of the genre, be warned: this is the film equivalent of institutional food—served cold, unmistakably bland, instantly forgotten. Do yourself a favor: parole yourself to something better.